Yesterday, David Barton came to Thomas Jefferson’s rescue after a statue of the third president was defaced last weekend at Jefferson’s alma mater the College of William & Mary. Those who attacked the statue painted Jefferson’s hands red and wrote “slave owner” nearby.

Indeed, Jefferson was a slave owner at the same time he made some steps to end the slave trade. He signed the bill ending the slave trade in 1808. However, Jefferson owned slaves at the same time he signed that bill into law.

When it comes to his positions and actions relating to slavery, Jefferson remains an enigma. However, Barton considers Jefferson to be a civil rights hero. Barton told WND:

Barton argues Thomas Jefferson was a major opponent of slavery who worked all his life to end the practice. He also contends Jefferson was not the “racist” he has been portrayed as.

“Students today need to study Thomas Jefferson’s own writings and actions rather than listening to the blatantly false claims of those who hate America and her Founders,” he advised.

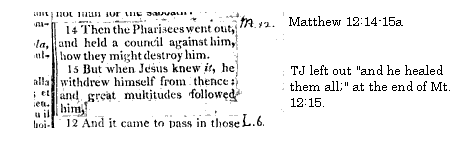

I agree that we need to study Jefferson’s own writings. In fact, I have some for you below.

Read Jefferson’s opinions of African slaves from his Notes on the State of Virginia, pages 264-267. Partly correct, Barton tells us that Jefferson wanted to free the slaves. What Barton doesn’t tell you is that Jefferson didn’t want the freed slaves to have American civil rights. He wanted them sent elsewhere because he didn’t think blacks and whites were of equal ability. Jefferson wanted America to be white. Jefferson wrote:

To emancipate all slaves born after passing the act. The bill reported by the revisors does not itself contain this proposition; but an amendment containing it was prepared, to be offered to the legislature whenever the bill should be taken up, and further directing, that they should continue with their parents to a certain age, then be brought up, at the public expence, to tillage, arts or sciences, according to their geniusses, till the females should be eighteen, and the males twenty-one years of age, when they should be colonized to such place as the circumstances of the time should render most proper, sending them out with arms, implements of houshold and of the handicraft arts, feeds, pairs of the useful domestic animals, &c. to declare them a free and independant people, and extend to them our alliance and protection, till they shall have acquired strength; and to send vessels at the same time to other parts of the world for an equal number of white inhabitants; to induce whom to migrate hither, proper encouragements were to be proposed.

It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expence of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race. — To these objections, which are political, may be added others, which are physical and moral. The first difference which strikes us is that of colour. Whether the black of the negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarf-skin, or in the scarf-skin itself; whether it proceeds from the colour of the blood, the colour of the bile, or from that of some other secretion, the difference is fixed in nature, and is as real as if its seat and cause were better known to us. And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races? Are not the fine mixtures of red and white, the expressions of every passion by greater or less suffusions of colour in the one, preferable to that eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immoveable

–265–

veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race? Add to these, flowing hair, a more elegant symmetry of form, their own judgment in favour of the whites, declared by their preference of them, as uniformly as is the preference of the Oranootan for the black women over those of his own species. The circumstance of superior beauty, is thought worthy attention in the propagation of our horses, dogs, and other domestic animals; why not in that of man? Besides those of colour, figure, and hair, there are other physical distinctions proving a difference of race. They have less hair on the face and body. They secrete less by the kidnies, and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a very strong and disagreeable odour. This greater degree of transpiration renders them more tolerant of heat, and less so of cold, than the whites. Perhaps too a difference of structure in the pulmonary apparatus, which a late ingenious experimentalist has discovered to be the principal regulator of animal heat, may have disabled them from extricating, in the act of inspiration, so much of that fluid from the outer air, or obliged them in expiration, to part with more of it. They seem to require less sleep. A black, after hard labour through the day, will be induced by the slightest amusements to sit up till midnight, or later, though knowing he must be out with the first dawn of the morning. They are at least as brave, and more adventuresome. But this may perhaps proceed from a want of forethought, which prevents their seeing a danger till it be present. When present, they do not go through it with more coolness or steadiness than the whites. They are more ardent after their female: but love seems with them to be more an eager desire, than a tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation. Their griefs are transient. Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them. In general, their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection. To this must be ascribed their disposition to sleep when abstracted from their diversions, and unemployed in labour. An animal whose body is at rest, and who does not reflect, must be disposed to sleep

–266–

of course. Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous. It would be unfair to follow them to Africa for this investigation. We will consider them here, on the same stage with the whites, and where the facts are not apocryphal on which a judgment is to be formed. It will be right to make great allowances for the difference of condition, of education, of conversation, of the sphere in which they move. Many millions of them have been brought to, and born in America. Most of them indeed have been confined to tillage, to their own homes, and their own society: yet many have been so situated, that they might have availed themselves of the conversation of their masters; many have been brought up to the handicraft arts, and from that circumstance have always been associated with the whites. Some have been liberally educated, and all have lived in countries where the arts and sciences are cultivated to a considerable degree, and have had before their eyes samples of the best works from abroad. The Indians, with no advantages of this kind, will often carve figures on their pipes not destitute of design and merit. They will crayon out an animal, a plant, or a country, so as to prove the existence of a germ in their minds which only wants cultivation. They astonish you with strokes of the most sublime oratory; such as prove their reason and sentiment strong, their imagination glowing and elevated. But never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never see even an elementary trait of painting or sculpture. In music they are more generally gifted than the whites with accurate ears for tune and time, and they have been found capable of imagining a small catch. Whether they will be equal to the composition of a more extensive run of melody, or of complicated harmony, is yet to be proved. Misery is often the parent of

267–

the most affecting touches in poetry. — Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry. Love is the peculiar ;oestrum of the poet. Their love is ardent, but it kindles the senses only, not the imagination. Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately; but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism. The heroes of the Dunciad are to her, as Hercules to the author of that poem. Ignatius Sancho has approached nearer to merit in composition; yet his letters do more honour to the heart than the head. They breathe the purest effusions of friendship and general philanthropy, and shew how great a degree of the latter may be compounded with strong religious zeal. He is often happy in the turn of his compliments, and his stile is easy and familiar, except when he affects a Shandean fabrication of words. But his imagination is wild and extravagant, escapes incessantly from every restraint of reason and taste, and, in the course of its vagaries, leaves a tract of thought as incoherent and eccentric, as is the course of a meteor through the sky. His subjects should often have led him to a process of sober reasoning: yet we find him always substituting sentiment for demonstration. Upon the whole, though we admit him to the first place among those of his own colour who have presented themselves to the public judgment, yet when we compare him with the writers of the race among whom he lived, and particularly with the epistolary class, in which he has taken his own stand, we are compelled to enroll him at the bottom of the column. This criticism supposes the letters published under his name to be genuine, and to have received amendment from no other hand; points which would not be of easy investigation. The improvement of the blacks in body and mind, in the first instance of their mixture with the whites, has been observed by every one, and proves that their inferiority is not the effect merely of their condition of life.

Later in the WND piece, Barton says:

Yes, Jefferson owned slaves, but he repeatedly tried to pass laws not only to free his own slaves, but all those in his state of Virginia. Sadly, he was unsuccessful. And state law would not allow him to free his own slaves. History clearly shows that Jefferson should be seen as an early anti-slavery advocate who was far ahead of his time in his home state.

In fact, after an early attempt to emancipate slaves in order to send them somewhere else, Jefferson had little to do with emancipation efforts in VA. After Virginia slave owners got the right to free slaves in 1782, Jefferson did not move to emancipate his slaves. Barton is simply wrong on this point. While it may have been difficult financially for Jefferson to free his slaves, he was legally allowed to do so after 1782. History clearly shows that many Virginia slave owners emancipated slaves while Thomas Jefferson did not. Jefferson talks about his early efforts on behalf of African slaves in the passage cited above and repeated below:

To emancipate all slaves born after passing the act. The bill reported by the revisors does not itself contain this proposition; but an amendment containing it was prepared, to be offered to the legislature whenever the bill should be taken up, and further directing, that they should continue with their parents to a certain age, then be brought up, at the public expence, to tillage, arts or sciences, according to their geniusses, till the females should be eighteen, and the males twenty-one years of age, when they should be colonized to such place as the circumstances of the time should render most proper, sending them out with arms, implements of houshold and of the handicraft arts, feeds, pairs of the useful domestic animals, &c. to declare them a free and independant people, and extend to them our alliance and protection, till they shall have acquired strength; and to send vessels at the same time to other parts of the world for an equal number of white inhabitants; to induce whom to migrate hither, proper encouragements were to be proposed. (emphasis added)

Yes, if this bill had passed, the slaves would have been freed but they would have been colonized to another location (he favored Santo Domingo) and exchanged for white people living elsewhere. Jefferson’s plan wasn’t perhaps as harsh as others who wanted slavery to persist in this country, but he certainly maintained views that can only be described as a racist. Jefferson’s tenure as a slave owner also requires scrutiny. He sent slave catchers after runaway slaves and profited from the babies born to slave women. These facts should not be minimized.

Barton’s whitewash of Jefferson doesn’t serve anyone well. When Barton obscures the truth, he gives ammunition to those who wish to obscure the positive contributions that Jefferson made to the common good. We must see historical figures in their time and place but not change the facts to make them fit our wishes. Jefferson’s racist words should be studied so that we can understand the errors he made, why he made them, and seek ways to avoid making them again.