The following information comes from session two of the Institute on the Constitution’s course which is this week completing a 12-week run on the NRB network. Because I was unable to secure permission to show video clips of the course, I was reluctant at the time to discuss the errors in the presentation. However, this misrepresentation of a study by Lutz and Hyneman is worth pointing out. In his effort to prove that the framers of the Constitution deliberately set out to base the Constitution on Biblical law, Peroutka cited a study of founding era documents by Donald Lutz.* Here is Peroutka’s description at about 25 minutes into the session:

I want to talk for a minute about this study that was done back in the 1980s by men named Lutz and Hyneman. And they did this study of the sources of authority that were used by these 55 men, these framers. They went back and looked at letters, public papers of these 55 men, everything they could find. They reviewed 15,000 items, 3,154 references to other sources. So if they wrote a letter and they quoted something, who were they quoting? In other words, what were they looking to as the source of authority? And what they found with this was 34% of the quotations of the framers in their writings came from the revealed law, came from the Scripture, came from the Bible, 34%, one-third of all their quotations came from the Bible. And actually if you add in the second, the second highest source of authority was Baron Montesquieu who was a Catholic and that was about 8% and Blackstone would have been about 7%. So if you take these 34% and those 15, you have almost 50%.

This is incorrect and presented in such a way as to be highly misleading. Here is what Donald Lutz said about his methodology:

Approximately ten years ago this author set out with Charles S. Hyneman to read comprehensively the political writings of Americans published between 1760 and 1805. This period was defined as the “founding era” during which the theory and institutions informing the state and national constitutions took final form. Reviewing an estimated 15,000 items, and reading closely some 2,200 items with explicitly political content, we identified and rated those with the most significant and coherent theoretical content. Included were all books, pamphlets, newspaper articles, and monographs printed for public consumption. Excluded was anything that remained private and so did not enter public consciousness, such as letters and notes. Essentially we exhausted all those items reproduced in collections published by historians, the newspapers available in the Library of Congress, the early American imprints held by the Lilly Library at Indiana University, the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and the Library of Congress. Finally, we examined the two volumes of Shipton and Mooney, National Index of American Imprints, for items in the Evans collection of early American imprints on microcard. The resulting sample has 916 items, which include 3,154 references to 224 different individuals. The sample includes all of the Anti-Federalist pieces identified by Storing (1981) plus 33 more, for a total of 197 Anti-Federalist pieces. It also includes 190 items written by Federalists. Most of these items are identified in Storing (1976); the rest can be found in Hyneman and Lutz (1983), which lists 515 pieces. Although not exhaustive, the sample is by far the largest ever assembled, and neither excludes nor emphasizes any point of view. Excluding the proceedings of legislatures and conventions, upon which the sample does not draw, the sample represents approximately one-third of all public political writings longer than 2,000 words published between 1760 and 1805. Also, the distribution of published writings during the era is roughly proportional to the number of citations for each decade. (p.191)

See the differences? Peroutka said Lutz and Hyneman studied the writings of the 55 framers. Not so. Lutz and Hyneman studied the “political writings of Americans published between 1760 and 1805.” Their review was not limited to framers. Furthermore, Peroutka said Lutz and Hyneman read the framers’ letters. Again not so. They specifically indicated that they did not read letters that were private.

Peroutka told his audience that the study was of “the sources of authority” used by the framers. However, Lutz and Hyneman defined what they meant by influence and it does not correspond to Peroutka’s description.

Thus, “influence” is used here in a broad sense. Only close textual analysis can establish the presence of specific ideas in a text, and comparative textual analysis the probable source of the ideas. A weakness of the citation-count method is that it cannot distinguish among citations that represent the borrowing of an idea, the adapting of an idea, the approval of an idea, the opposition to an idea, or an appeal to authority. (p. 191)

These are crucial differences. Peroutka wants us to believe that the framers favorably referenced the Bible about half the time as a source of authority in constructing their political philosophy. He wants us to believe that the Bible was the basis for the founding documents. However, the general aim of Lutz’s study was to document the reading material available during the founding era which might then give clues about the diversity of influences on American political thought during that era. With an exception I will explain below, Lutz and Hyneman did not limit their study to the framers or attempt to determine how any of the sources were used by them.

The high percentage of Biblical references is interesting and is worth a longer look. Lutz provided additional context by noting that the high percentage of Biblical citations in printed material at the time was due to the large number of reprinted sermons made available by ministers. Lutz spoke to that point in his methods section:

If we ask what book was most frequently cited by Americans during the founding era, the answer somewhat surprisingly is: the Book of Deuteronomy. From Table 1 we can see that the biblical tradition is most prominent among the citations. Anyone familiar with the literature will know that most of these citations come from sermons reprinted as pamphlets; hundreds of sermons were reprinted during the era, amounting to at least 10% of all pamphlets published. These reprinted sermons accounted for almost three-fourths of the biblical citations, making this nonsermon source of biblical citations roughly as important as the Classical or Common Law categories. (p 192)

Note that Lutz did not reference the framers; he studied the writings of “Americans.” The type of citation is also important to note. Of course the Bible would be cited in sermons; but that doesn’t mean that the framers read or referenced them or that the sermons figured decisively in the framers’ political opinions and writings.

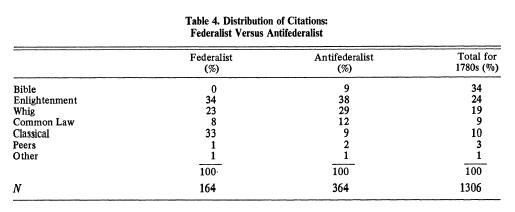

In addition to being inaccurate, his treatment of the study is incomplete. Peroutka fails to point out the most important part of the study for students of the Constitution. On page 194 of the study, Lutz charts the analysis of the citations in the Federalist and Antifederalist papers.

Note that the Bible was not cited at all by the Federalists. Those opposed to the Constitution, the Antifederalists cited the Bible infrequently. I wonder why Peroutka left this part out.

Peroutka continues to say that Blackstone and Montesquieu based their ideas on the Bible and so the framers influence from the Bible is closer to 50%. As noted, he gets the study wrong via his reference to the framers, and he is very far off on Montesquieu. While Montesquieu had respect for Christianity, he had respect for many belief systems and wrote that even false beliefs can have good political consequences. His interest in religion was pragmatic and political and even wrote that religious teachings seldom make a good foundation for civil law, exactly the opposite of the premise of this course.

There are other problems like this throughout the course.

*Donald Lutz. (1984). The Relative Influence of European Writers on Late Eighteenth-Century American Political Thought. The American Political Science Review, 78, 189-197.