TJ was born on April 13, 1743. So what can you get a founder of our country who is experiencing his reward?

1. You can spread this post around Twitter and Facebook: David Barton’s Jefferson Lies: The Immigration and Healthcare Edition. This post illustrates how far David Barton will go to misrepresent Jefferson to suit Barton’s political views. Barton adds and subtracts words from our third president’s 1805 address to Congress in order to support Barton’s preferred narrative. Jefferson’s not here to set him straight, so you can help out.

In honor of Jefferson’s birthday, Barton should admit what he did and apologize.

2. You can get yourself or a friend a copy of critically acclaimed Getting Jefferson Right authored by Michael Coulter and me (now only $2.99 for the e-book). The book debunks many of key claims of Christian nation advocates (Barton is the most prominent among them) about Jefferson.

Category: Getting Jefferson Right

How to Use Bad Situations to Teach Good Lessons – David Barton's The Jefferson Lies in Foundations of History

Most of my professor colleagues use negative events in the news to teach various lessons. For instance, I have used Mark Driscoll’s plagiarism to teach my students about plagiarism. I feel sure many profs have used Monica Crowley’s plagiarism to teach about that subject. I also refer to David Barton’s faux doctorate to help my students understand how to simulate expertise.

With this post, I hope to start a series of occasional articles which illustrate how one may turn a negative situation into a good lesson. The first contributor is Robert Clemm, Associate Professor of History at Grove City College. The event Rob uses to teach good lessons is the removal from publication of David Barton’s The Jefferson Lies. Below, Rob answers my questions about how he uses The Jefferson Lies to teach good history lessons.

WT: In what course is the activity used?

RC: I incorporate David Barton, and The Jefferson Lies debate, into my Foundations of History course. This is a course that is designed for non-majors at an introductory level but is, in reality, more of a “low-level historiography” course as I’ve never been able to conceive of any other way of teaching it. I broadly divide the class into thirds. The first third is an exploration of how historians view themselves and their discipline utilizing John Lewis Gaddis’ The Landscape of History. The second “third” is the historiography and methodology section in which they read through John H. Arnold’s History: A Very Short Introduction, as well as major figures (Herodotus, Thucydides, Bede) in the development of history. The last third is a “where history is going” section in which we discuss newer (post-1950) approaches towards history such as Gender, Oral, Material Culture, and Digital History.

Barton is integrated into the course at the tail end of my second “third” of the course. After the students have gone through the historiography section, to the point at which Leopold von Ranke seems to establish the “model” for how historians works, Arnold’s book continues by assessing some of the difficulties historians face in interpreting and writing about the past. After they have finished with his book I wanted to try to give them a few opportunities to wrestle with the difficulties of history and apply some of what they had learned. This is also a bit of a skill-based approach as their final paper is an assessment of the work of a historian and I try to give them a few weeks to practice that sort of assessment in a class context. During the shorter week we always have due to break, I have them read and assess a chapter from [Larry Schweikart’s] A Patriot’s History of the United States and [Howard Zinn’s] A People’s History of the United States. Coming back to back, students are really able to see the contrast between two ‘textbooks’ that might as well be describing two different planets for as much as their books have in common. I’ve found that to be a very eye-opening exercise to many students given that they tend to associate any textbook they are given as being near holy writ in terms of truthfulness. I also find that this exercise, which underscores the power of interpretation by historians of the past, paves the way for them to be more receptive to an analysis of David Barton.

WT: Describe the activity.

RC: After the short week, I then spend a whole week (M-W-F classes) on David Barton in the following manner. On Monday I introduce David Barton and pitch him to about as high as I possibly can. In his commitment to primary sources, I describe him as a modern-day antiquarian and in his desire to challenge conventional/received wisdom, I liken him to Thucydides. I may lay it on a bit thick, but generally I’m trying to present him in the best of all possible lights for my students. I’m helped that most of my “lecture” consists of two long interviews David Barton had with Glenn Beck. Not only does this allow Barton to be presented “in his own words,” literally in this case, he also presents most of his main arguments in The Jefferson Lies. To be honest, I intend this day to be a bit of a “set-up” for my students. I’ve had several students, at the end of the week, relate they had been excited about his work and told friends about what they were learning which is precisely my goal for that day.

On Wednesday, I have invited Michael Coulter, your co-author [Getting Jefferson Right], to come speak to my class. He has graciously done this going on 5 years now, and I do appreciate his willingness to do so. Given that on Monday I praised Barton to the heavens I think it is helpful to hear from someone else in providing a contrary voice. In this class I introduce Dr. Coulter and let him speak about his experience with The Jefferson Lies and writing Getting Jefferson Right. He tends to open by describing where he was when he heard Barton’s book had been pulled by Thomas Nelson – I believe he was helping someone paint a room? – and then backtracks through the book itself. In doing so he tends to hit on problems/critiques of points Barton had raised with Beck, but also highlights other issues such as his obfuscation of the slave laws of Virginia through ellipses. As he is lecturing, I tend to just sit back and ‘enjoy’ watching my students suffer a small version of intellectual whiplash.

I also appreciate that he highlights for the students that this is not a mere academic squabble but one Barton has largely brought on himself by claiming to be the Christian historian against which we should all be measured. As Dr. Coulter has said numerous times in my class, by claiming that mantle he is calling into question the work of hundreds of historians, Christian and otherwise, and almost suggesting he is some neo-Gnostic with the keys to the truth of history. In constructing this week, therefore, I spend Monday “teeing up” the class for Michael and on Wednesday he knocks them straight towards confusion. After Wednesday’s class I send them a few links regarding the debate over pulling the books, some from his defenders and some from detractors.

On Friday we discuss not so much The Jefferson Lies itself but the debate surrounding it and whether or not Barton and his defenders had responded as befits being a part of the historical discipline. Given that one defender titled his work “Attacks on David Barton Same as Tactics of Saul Alinsky” and World Net Daily sums up the controversy as “The Anatomy of an American Book Banning” students generally agree that Barton failed to live up to proper historical standards.

WT: What lessons/objectives do you hope to teach with the activity?

RC: I use this week to try and accomplish a diverse number of objectives.

First, I hope that it helps students truly understand that history is a process and a debate. While they may have read that in Arnold’s work, and seen it on display in terms of the contrast between A Patriot’s and A People’s History, I think it is this week that really helps students understand why historians can get animated about a historical debate. Given that so nearly all the students are non-majors, I assume most of them come in with the sense that to choose to be a historian one must be a bit addled. Frankly don’t we know everything that happened? As one colleague commonly greets me in jest, “So, what’s new in history?” I think in discussing the debate over The Jefferson Lies they start to see why historians are passionate about their subject and discipline. In David Barton, so many of us see a charlatan who is not simply misappropriating the past for his own purposes, but also is misusing our entire field as a way of building a following. As they grapple with the implications of the debate I think they become invested as well and get a sense of why historians care so much about their subject as much as David Barton.

Second, I want them to recognize how a historical argument should go which is, frankly, the opposite of what has occurred with Barton and his book. I actually never make a categorical judgment on Barton’s book, telling my students that if they want to have an informed opinion they should read David Barton’s book and yours and then come to their own conclusion in light of the knowledge gained in the course. What I find much more valuable is helping them see why the debate over Barton’s book has “gone off the rails” and doesn’t fit with how historians should engage with one another. Engaging in ad hominem attacks, such as suggesting that you (Dr. Throckmorton) can’t have a valid critique because you aren’t a historian, has no place in how historians should undertake a common search for greater truth. I also highlight, since the debate over the book has become so politicized, that I never once complemented a student in that course for having the “proper Conservative answer” or the “proper Democratic question.” Barton complains endlessly about how he has been attacked by people who had been on “our team” [see the video below] and I instead point out that the only ‘team’ in history is the one trying to discover the truth.

Lastly, I want my students to recognize how historians have a true duty to the general public to present their best work by the standards of the discipline. In many ways this is the week that answers an implicit question as to why Arnold and Gaddis wrote so stridently about historians being humble in their search for the truth and to be constantly “tethered to and disciplined by the sources.” If previously they had thought all of that concern was academics trying to justify their existence, I think it comes home a bit more for them this week. It perhaps comes out most strongly if some students speak up for Barton’s defense and say that the book should have been left on the shelves in the “free market of ideas” so as to let the people decide. While the “marketplace of ideas” sounds good, I tend to press why it is insufficient. It’s a testament to the quality of our students that I don’t tend to have to spell out the answer. Invariably another student highlights how readers place their implicit trust in a historian that they have practiced good scholarship and will never go and check the veracity of someone’s footnotes. Students grasp that historians have to do the careful and dutiful work when in the archives and writing because what we present is trusted by those that read it. We have, in some regard, a trust with the general public that we need to uphold. When we fail to do that, as Barton has with The Jefferson Lies, we violate an implicit contract and cannot move the goalposts in suggesting the public should read it and make up their own minds. While it sounds wonderfully democratic, students realize it’s a sweet-sounding justification for passing off faulty scholarship.

WT: How is the activity received in class?

RC: I think overall it is the best week of the course. Our discussion on Friday tends to be one of the most animated of the course as students have, over the previous two classes, been primed to want to express their own opinion about the book and the controversy.

Beyond content I think it resonates because it comes at a point at the course when they realize they can critique historians and their works at a deeper level than they would have thought at the beginning of the semester. By that point they are aware of the nature of the historical discipline, how it developed, and some of the difficult balances historians have to strike between the reality of the past and representing it in their own work. After a week seeing the differences in American history, with A People’s History and A Patriot’s History, this gives them an opportunity to truly wrestle with questions of responsibility and interpretation. Given that I start the course by asking them why I even have a job when Wikipedia exists, I think it “clicks” for them that history is as much a matter of interpretation as a compendium of facts.

WT: Any other comments or reflections on using bad history to teach good history?

RC: At this point I will continue to use David Barton as I think his work, and the debate surrounding it, truly gets at a number of points I don’t think I could express as easily with any other topic. I also don’t think anyone should feel concerned about students picking up bad habits since Barton and his defenders are so over the top – one student during a discussion asked “Does he know he’s arguing like a 5th grader?” – that it really grates on them regardless of their opinion of the content of his book.

My biggest surprise so far – and perhaps this speaks to your question – is that I’ve never had a defender/acolyte of Barton prepared to go 10 rounds defending him. Now, this could be for any number of reasons; self-selection by students, fear of ‘fighting’ the professor, or simply a desire not to speak in class. At the same time my hope is that students, when confronted with the facts of the Barton controversy, recognize the problems he poses and tend to agree with the critiques. For those concerned that simply presenting bad history might ‘corrupt’ their students, I think that this exercise proves that fear is unfounded. Even with a student body that might be more receptive than the norm to the conclusions of Barton’s work, if not his methods, they seem more than able to separate that from the justified historical critiques of his work.

This is the video that Dr. Clemm shows where Barton attacks me on issues other than history.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ni-LLnloEJQ[/youtube]

Many thanks to Dr. Clemm for sharing this activity.

Thomas Jefferson on the Importance of a Free Press (UPDATED with Trump’s Jefferson Quote)

Yesterday, President Donald Trump called the media (singling out the New York Times, CNN, ABC, CBS and NBC) the “enemy of the American people.”

The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 17, 2017

Trump’s barrage of animosity toward the press reminded me of the Sedition Act of 1798. I hope we do not go back to that dark day.

Thomas Jefferson was a staunch critic of the Sedition Act. Jefferson believed a free press was essential to republican government. In light of Donald Trump’s attacks on the press, I believe we should consider Jefferson’s thoughts on a free and independent press.

In a letter to James Currie in 1786, Jefferson complained that John Jay had been treated unfairly by the “public papers.” However, instead of calling the press the enemy of the people, Jefferson said:

In truth it is afflicting that a man [John Jay] who has past his life in serving the public, who has served them in every the highest stations with universal approbation, and with a purity of conduct which has silenced even party opprobrium, who tho’ poor has never permitted himself to make a shilling in the public employ, should yet be liable to have his peace of mind so much disturbed by any individual who shall think proper to arraign him in a newspaper. It is however an evil for which there is no remedy. Our liberty depends on the freedom of the press, and that cannot be limited without being lost. To the sacrifice, of time, labor, fortune, a public servant must count upon adding that of peace of mind and even reputation. (emphasis added)

Even though Jefferson believed the papers to be wrong, he asserted that the liberty of the nation depends on the freedom of the press without limitation.

Three years later, Jefferson wrote to Edward Carrington from Paris with a similar sentiment.

The people are the only censors of their governors: and even their errors will tend to keep these to the true principles of their institution. To punish these errors too severely would be to suppress the only safeguard of the public liberty. The way to prevent these irregular interpositions of the people is to give them full information of their affairs thro’ the channel of the public papers, & to contrive that those papers should penetrate the whole mass of the people. The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter. But I should mean that every man should receive those papers & be capable of reading them. (emphasis added)

Jefferson was aware that the newspapers were sometimes wrong and he became exasperated with the press at times. However, he was sure that the liberty of the people depended on a free, if imperfect, press.

To Elbridge Gerry in 1799, Jefferson wrote:

I am for freedom of religion, & against all maneuvres to bring about a legal ascendancy of one sect over another: for freedom of the press, & against all violations of the constitution to silence by force & not by reason the complaints or criticisms, just or unjust, of our citizens against the conduct of their agents.

Jefferson himself was the subject of just and unjust criticism and yet he did not start a war with the press.

Jefferson maintained this view through his old age. To Marquis de Lafayette, Jefferson wrote in 1823:

Two dislocated wrists and crippled fingers have rendered writing so slow and laborious as to oblige me to withdraw from nearly all correspondence. not however from yours, while I can make a stroke with a pen. we have gone thro’ too many trying scenes together to forget the sympathies and affections they nourished. your trials have indeed been long and severe. when they will end is yet unknown, but where they will end cannot be doubted. alliances holy or hellish, may be formed and retard the epoch deliverance, may swell the rivers of blood which are yet to flow, but their own will close the scene, and leave to mankind the right of self government. I trust that Spain will prove that a nation cannot be conquered which determines not to be so. and that her success will be the turning of the tide of liberty, no more to be arrested by human efforts. whether the state of society in Europe can bear a republican government, I doubted, you know, when with you, a I do now. a hereditary chief strictly limited, the right of war vested in the legislative body, a rigid economy of the public contributions, and absolute interdiction of all useless expences, will go far towards keeping the government honest and unoppressive. but the only security of all is in a free press. the force of public opinion cannot be resisted, when permitted freely to be expressed. the agitation it produces must be submitted to. it is necessary to keep the waters pure. we are all, for example in agitation even in our peaceful country. for in peace as well as in war the mind must be kept in motion. (emphasis added).

Finally, Jefferson recognized that a free press provided information that some governments would deliberately keep from the people. We must have a free press to help provide a check on governmental power. To Charles Yancey in 1816, Jefferson wrote:

if a nation expects to be ignorant & free, in a state of civilisation, it expects what never was & never will be. the functionaries of every government have propensities to command at will the liberty & property of their constituents. there is no safe deposit for these but with the people themselves; nor can they be safe with them without information. where the press is free and every man able to read, all is safe. (emphasis added).

Although Jefferson was not a perfect man, he articulated natural rights as well as any Founder. A free press is a surely a right under the Constitution and it is a necessity for a free people. Trump’s assault on the media is unpatriotic and certainly unJeffersonian. Even when Jefferson disagreed with the press (and he often did), he was a statesman and patriot in his response to it. Today, we are in great need for statesmen and stateswomen to stand up for a free press.

UPDATE: During a rally in Florida today, Donald Trump quoted Jefferson as a critic of newspapers:

They have their own agenda and their agenda is not your agenda. In fact, Thomas Jefferson said, “nothing can be believed which is seen in a newspaper.” “Truth itself,” he said, “becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle,” that was June 14, my birthday, 1807. But despite all their lies, misrepresentations, and false stories, they could not defeat us in the primaries, and they could not defeat us in the general election, and we will continue to expose them for what they are, and most importantly, we will continue to win, win, win.

Trump pulled this quote from an 1807 letter to John Norvell. Indeed, Jefferson had many negative things to say about the press. However, he also said all of the things I quoted above. Trump only told his audience half of the story. Newspapers were more politically biased in Jefferson’s day than now and yet he defended the need for an independent press as a crucial means of protecting our liberties. Let’s recall that Jefferson’s harsh criticism came in private letters; Trump’s venom is delivered daily via Twitter. If Trump wants to be Jeffersonian, he must stop his public war on the press.

David Barton Again Whitewashes Thomas Jefferson Views on Race

Yesterday, David Barton came to Thomas Jefferson’s rescue after a statue of the third president was defaced last weekend at Jefferson’s alma mater the College of William & Mary. Those who attacked the statue painted Jefferson’s hands red and wrote “slave owner” nearby.

Indeed, Jefferson was a slave owner at the same time he made some steps to end the slave trade. He signed the bill ending the slave trade in 1808. However, Jefferson owned slaves at the same time he signed that bill into law.

When it comes to his positions and actions relating to slavery, Jefferson remains an enigma. However, Barton considers Jefferson to be a civil rights hero. Barton told WND:

Barton argues Thomas Jefferson was a major opponent of slavery who worked all his life to end the practice. He also contends Jefferson was not the “racist” he has been portrayed as.

“Students today need to study Thomas Jefferson’s own writings and actions rather than listening to the blatantly false claims of those who hate America and her Founders,” he advised.

I agree that we need to study Jefferson’s own writings. In fact, I have some for you below.

Read Jefferson’s opinions of African slaves from his Notes on the State of Virginia, pages 264-267. Partly correct, Barton tells us that Jefferson wanted to free the slaves. What Barton doesn’t tell you is that Jefferson didn’t want the freed slaves to have American civil rights. He wanted them sent elsewhere because he didn’t think blacks and whites were of equal ability. Jefferson wanted America to be white. Jefferson wrote:

To emancipate all slaves born after passing the act. The bill reported by the revisors does not itself contain this proposition; but an amendment containing it was prepared, to be offered to the legislature whenever the bill should be taken up, and further directing, that they should continue with their parents to a certain age, then be brought up, at the public expence, to tillage, arts or sciences, according to their geniusses, till the females should be eighteen, and the males twenty-one years of age, when they should be colonized to such place as the circumstances of the time should render most proper, sending them out with arms, implements of houshold and of the handicraft arts, feeds, pairs of the useful domestic animals, &c. to declare them a free and independant people, and extend to them our alliance and protection, till they shall have acquired strength; and to send vessels at the same time to other parts of the world for an equal number of white inhabitants; to induce whom to migrate hither, proper encouragements were to be proposed.

It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expence of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race. — To these objections, which are political, may be added others, which are physical and moral. The first difference which strikes us is that of colour. Whether the black of the negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarf-skin, or in the scarf-skin itself; whether it proceeds from the colour of the blood, the colour of the bile, or from that of some other secretion, the difference is fixed in nature, and is as real as if its seat and cause were better known to us. And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races? Are not the fine mixtures of red and white, the expressions of every passion by greater or less suffusions of colour in the one, preferable to that eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immoveable

–265–

veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race? Add to these, flowing hair, a more elegant symmetry of form, their own judgment in favour of the whites, declared by their preference of them, as uniformly as is the preference of the Oranootan for the black women over those of his own species. The circumstance of superior beauty, is thought worthy attention in the propagation of our horses, dogs, and other domestic animals; why not in that of man? Besides those of colour, figure, and hair, there are other physical distinctions proving a difference of race. They have less hair on the face and body. They secrete less by the kidnies, and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a very strong and disagreeable odour. This greater degree of transpiration renders them more tolerant of heat, and less so of cold, than the whites. Perhaps too a difference of structure in the pulmonary apparatus, which a late ingenious experimentalist has discovered to be the principal regulator of animal heat, may have disabled them from extricating, in the act of inspiration, so much of that fluid from the outer air, or obliged them in expiration, to part with more of it. They seem to require less sleep. A black, after hard labour through the day, will be induced by the slightest amusements to sit up till midnight, or later, though knowing he must be out with the first dawn of the morning. They are at least as brave, and more adventuresome. But this may perhaps proceed from a want of forethought, which prevents their seeing a danger till it be present. When present, they do not go through it with more coolness or steadiness than the whites. They are more ardent after their female: but love seems with them to be more an eager desire, than a tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation. Their griefs are transient. Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them. In general, their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection. To this must be ascribed their disposition to sleep when abstracted from their diversions, and unemployed in labour. An animal whose body is at rest, and who does not reflect, must be disposed to sleep

–266–

of course. Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous. It would be unfair to follow them to Africa for this investigation. We will consider them here, on the same stage with the whites, and where the facts are not apocryphal on which a judgment is to be formed. It will be right to make great allowances for the difference of condition, of education, of conversation, of the sphere in which they move. Many millions of them have been brought to, and born in America. Most of them indeed have been confined to tillage, to their own homes, and their own society: yet many have been so situated, that they might have availed themselves of the conversation of their masters; many have been brought up to the handicraft arts, and from that circumstance have always been associated with the whites. Some have been liberally educated, and all have lived in countries where the arts and sciences are cultivated to a considerable degree, and have had before their eyes samples of the best works from abroad. The Indians, with no advantages of this kind, will often carve figures on their pipes not destitute of design and merit. They will crayon out an animal, a plant, or a country, so as to prove the existence of a germ in their minds which only wants cultivation. They astonish you with strokes of the most sublime oratory; such as prove their reason and sentiment strong, their imagination glowing and elevated. But never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never see even an elementary trait of painting or sculpture. In music they are more generally gifted than the whites with accurate ears for tune and time, and they have been found capable of imagining a small catch. Whether they will be equal to the composition of a more extensive run of melody, or of complicated harmony, is yet to be proved. Misery is often the parent of

267–

the most affecting touches in poetry. — Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry. Love is the peculiar ;oestrum of the poet. Their love is ardent, but it kindles the senses only, not the imagination. Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately; but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism. The heroes of the Dunciad are to her, as Hercules to the author of that poem. Ignatius Sancho has approached nearer to merit in composition; yet his letters do more honour to the heart than the head. They breathe the purest effusions of friendship and general philanthropy, and shew how great a degree of the latter may be compounded with strong religious zeal. He is often happy in the turn of his compliments, and his stile is easy and familiar, except when he affects a Shandean fabrication of words. But his imagination is wild and extravagant, escapes incessantly from every restraint of reason and taste, and, in the course of its vagaries, leaves a tract of thought as incoherent and eccentric, as is the course of a meteor through the sky. His subjects should often have led him to a process of sober reasoning: yet we find him always substituting sentiment for demonstration. Upon the whole, though we admit him to the first place among those of his own colour who have presented themselves to the public judgment, yet when we compare him with the writers of the race among whom he lived, and particularly with the epistolary class, in which he has taken his own stand, we are compelled to enroll him at the bottom of the column. This criticism supposes the letters published under his name to be genuine, and to have received amendment from no other hand; points which would not be of easy investigation. The improvement of the blacks in body and mind, in the first instance of their mixture with the whites, has been observed by every one, and proves that their inferiority is not the effect merely of their condition of life.

Later in the WND piece, Barton says:

Yes, Jefferson owned slaves, but he repeatedly tried to pass laws not only to free his own slaves, but all those in his state of Virginia. Sadly, he was unsuccessful. And state law would not allow him to free his own slaves. History clearly shows that Jefferson should be seen as an early anti-slavery advocate who was far ahead of his time in his home state.

In fact, after an early attempt to emancipate slaves in order to send them somewhere else, Jefferson had little to do with emancipation efforts in VA. After Virginia slave owners got the right to free slaves in 1782, Jefferson did not move to emancipate his slaves. Barton is simply wrong on this point. While it may have been difficult financially for Jefferson to free his slaves, he was legally allowed to do so after 1782. History clearly shows that many Virginia slave owners emancipated slaves while Thomas Jefferson did not. Jefferson talks about his early efforts on behalf of African slaves in the passage cited above and repeated below:

To emancipate all slaves born after passing the act. The bill reported by the revisors does not itself contain this proposition; but an amendment containing it was prepared, to be offered to the legislature whenever the bill should be taken up, and further directing, that they should continue with their parents to a certain age, then be brought up, at the public expence, to tillage, arts or sciences, according to their geniusses, till the females should be eighteen, and the males twenty-one years of age, when they should be colonized to such place as the circumstances of the time should render most proper, sending them out with arms, implements of houshold and of the handicraft arts, feeds, pairs of the useful domestic animals, &c. to declare them a free and independant people, and extend to them our alliance and protection, till they shall have acquired strength; and to send vessels at the same time to other parts of the world for an equal number of white inhabitants; to induce whom to migrate hither, proper encouragements were to be proposed. (emphasis added)

Yes, if this bill had passed, the slaves would have been freed but they would have been colonized to another location (he favored Santo Domingo) and exchanged for white people living elsewhere. Jefferson’s plan wasn’t perhaps as harsh as others who wanted slavery to persist in this country, but he certainly maintained views that can only be described as a racist. Jefferson’s tenure as a slave owner also requires scrutiny. He sent slave catchers after runaway slaves and profited from the babies born to slave women. These facts should not be minimized.

Barton’s whitewash of Jefferson doesn’t serve anyone well. When Barton obscures the truth, he gives ammunition to those who wish to obscure the positive contributions that Jefferson made to the common good. We must see historical figures in their time and place but not change the facts to make them fit our wishes. Jefferson’s racist words should be studied so that we can understand the errors he made, why he made them, and seek ways to avoid making them again.

Eric Metaxas and David Barton: Show Me the Miracles

On Tuesday, I posted an audio clip of David Barton on Eric Metaxas’ radio show talking about the two times when Thomas Jefferson cut up the Gospels to create an extraction of the morals of Jesus. During Jefferson’s first term, he revealed his beliefs about Christianity to some of his closer friends and in the process decided to cut out of the Gospels portions which Jefferson believed were actually from Jesus, leaving the rest behind.

On Tuesday, I posted an audio clip of David Barton on Eric Metaxas’ radio show talking about the two times when Thomas Jefferson cut up the Gospels to create an extraction of the morals of Jesus. During Jefferson’s first term, he revealed his beliefs about Christianity to some of his closer friends and in the process decided to cut out of the Gospels portions which Jefferson believed were actually from Jesus, leaving the rest behind.

On the program, Barton told Metaxas a made up story about what Jefferson did and mixed in a little truth with some error to create a flawed picture. Metaxas took it in without question. In my Tuesday post, I debunked Barton’s story about how Jefferson got the idea to cut up the Gospels and today I want to set the stage for what is a more difficult aspect of this story: identifying the verses Jefferson included in his first effort to extract the true teachings of Jesus from the Gospels.

The reason it is more difficult to know what Jefferson included in his 1804 effort is because the original manuscript has been lost. There isn’t a copy we can look at. The version completed sometime after 1820 is the one commonly known as the Jefferson Bible. That version can be purchased from the Smithsonian and viewed online.

Do We Know What Jefferson Cut Out of the Gospels?

Reproductions of the 1804 version exist but for reasons I will address in this series, there are some disputed verses which Jefferson may or may not have included. There really is no way to be sure.

Jefferson mentioned both versions in a letter to Adrian Van Der Kemp in 1816, Jefferson wrote about both extractions:

I made, for my own satisfaction, an Extract from the Evangelists of the texts of his morals, selecting those only whose style and spirit proved them genuine, and his own: and they are as distinguishable from the matter in which they are imbedded as diamonds in dunghills. a more precious morsel of ethics was never seen. it was too hastily done however, being the work of one or two evenings only, while I lived at Washington, overwhelmed with other business: and it is my intention to go over it again at more leisure. this shall be the work of the ensuing winter. I gave it the title of ‘the Philosophy of Jesus extracted from the text of the Evangelists.’

The “work of one or two evenings only, while I lived in Washington, overwhelmed with other business” is a reference to his 1804 effort which was done for his “own satisfaction.” When he referred to “his intention to go over it again at more leisure” in an “ensuing winter,” he referred to the version he later completed sometime after 1820. It should be obvious from this letter that Jefferson viewed the second project as a completion of the 1804 work which was “too hastily done” while attending to his presidential duties. Jefferson does not refer to them as two separate projects with separate purposes. Rather, the 1804 version was more like a trial run and the latter was the product of more time and concentration.

How Do We Know What Verses Jefferson Included?

There are two primary sources for our knowledge of what verses Jefferson included. First, ever meticulous and organized, Jefferson prepared a listing of texts he planned to include. Michael Coulter and I included images of the originals (housed at the University of VA) in our book Getting Jefferson Right. The second source is the cut-up Bibles Jefferson used to cut out the verses he pasted together to form the 1804 version. In contrast to Barton’s claim, Jefferson didn’t cut out only Jesus’ words and he certainly didn’t cut them all out and paste them end to end.

Although these sources are critically important, they are not sufficient to be sure about what Jefferson included. A major barrier to certainty is that Jefferson cut out some verses which were not listed in his table of texts. This can be discerned by reviewing the parts of the Gospels which were cut out. What can never be known for sure is why Jefferson cut out more verses than he intended. We cannot assume that he intended to cut out any verse other than what he listed in his table of verses. However, we cannot assume he didn’t decide as he was doing it that he wanted to include something on the fly.

There are good arguments to be made for both possibilities. Jefferson said he did the 1804 version “too hastily.” Thus, he may have made some errors in cutting and cut too many verses or simply cut some in error from the wrong page. Anyone who has literally cut and pasted any kind of craft project can probably relate to that possibility.

On the other hand, it is certainly plausible to think that Jefferson changed his mind as he read through the Gospels again. He may have decided he wanted a particular verse that he didn’t include in the table. Nothing would have stopped him from clipping it.

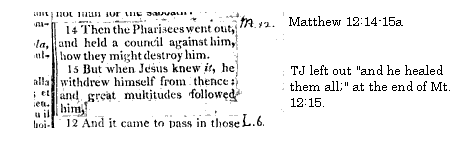

Another possibility exists for the 1804 version which we know is true for the 1820 version. At times, Jefferson surgically extracted miraculous content from within a verse. In other words, he cut out a verse from the Gospels but when he included it in his manuscript, he only included a part of the verse. For instance, Jefferson included Matthew 12:15 in his 1820 version, but he left out the end of the verse where the healing took place.*

Mt. 12:15 in entirety reads:

But when Jesus knew it, he withdrew himself from thence: and great multitudes followed him, and he healed them all.

Jefferson intentionally left out the healing (“and he healed them all”) even though he included the verse. Clearly, it is not enough for us today to know what Jefferson cut out of those Gospels in 1804. For a perfect reconstruction, we would have to know what parts of the verses he included. A few disputed verses do have some miraculous content but that is no guarantee that Jefferson included that content in his compilation. We know he used partial verses in his second attempt; it is very plausible that he did the same thing the first time around.

Barton’s story to Metaxas completely glosses over these facts. If we really want to get inside Jefferson’s thinking about Jesus in the Gospels in 1804, we should first look at the table of texts he constructed (click here to examine those tables). Then we can look at the verses which Jefferson cut out but didn’t list. However, we must approach those disputed verses carefully. We don’t know why he cut them out and we don’t know what parts, if any, he actually included.

Barton Also Uses a Flawed Secondary Source

In The Jefferson Lies, Barton links to two secondary sources for his information about what is in the 1804 version. In at least one case, the source has a major error which we point out in Getting Jefferson Right. In the next post, I will address that secondary source error.

I challenge Eric Metaxas to bring on an actual historian and/or me to discuss the issues raised recently about his book, If You Can Keep It or this series.

*Jefferson Bible, ch 1:59-60.