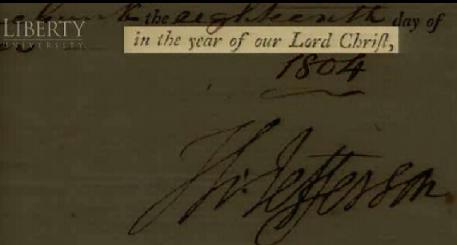

On September 9, David Barton spoke to students at Liberty University during their chapel service. Last week I addressed several claims Barton made during the first five minutes of his talk. Today, I want to follow up with more detail about Barton’s claim that Thomas Jefferson and other early Presidents signed official presidential documents with the closing “In the year of our Lord Christ.” Barton points to this phrase as evidence that the early Presidents “had Jesus Christ in the center of what they did.”

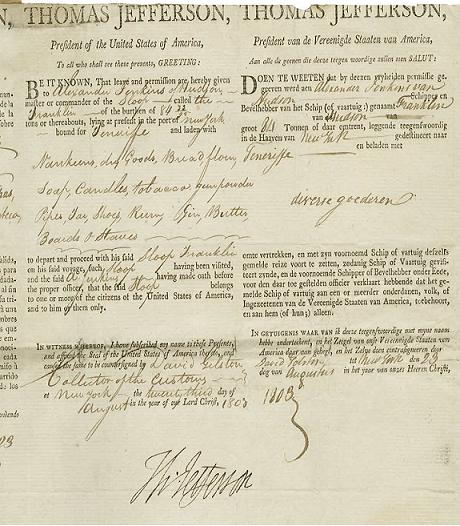

Earlier this year, I demonstrated that a document on the Wallbuilders website dated 1807 and signed by Thomas Jefferson is a passport, also called a sea letter, needed by ships at the time to indicate that they were no threat to friend or foe as a combat ship. The wording of the sea letter signed by Jefferson was required by a treaty with Holland. Sea letters were in common use, so much so that Congress authorized the printing of a form for this use with the treaty language preprinted. The language specified in the treaty with Holland included the phrase, “In the year of our Lord Christ” and only required the person completing the form to include information about the ship, the cargo, the destination and the correct date.

This was a perfunctory duty of the President at the time, causing John Adams to lament to his wife Abigail in a letter that his fate was to sign “Thousands of sea letters, Mediterranean passes, and commissions and patents to sign; no company — no society.”

Thomas Jefferson was once asked about the proper use of a sea letter by Secretary of Treasury Albert Gallatin. In his January 26, 1805 reply, it is clear that the document is not something he or the Congress developed, saying

The question arising on Mr. Simons’ letter of January 10th is whether sea-letters shall be given to the vessels of citizens neither born nor residing in the United States. Sea-letters are the creatures of treaties. No act of the ordinary legislature requires them. The only treaties now existing with us, and calling for them, are those with Holland, Spain, Prussia, and France. In the two former we have stipulated that when the other party shall be at war, the vessels belonging to our people shall be furnished with sea-letters; in the two latter that the vessels of the neutral party shall be so furnished. France being now at war, the sea-letter is made necessary for our vessels; and consequently it is our duty to furnish them. (my emphasis)

If you search through the Annals of Congress (1774-1875), you will find 8 citations with the exact phrase, “in the year of our Lord Christ.” All of them are used in a treaty (Holland, Morocco, Japan). The exact form for the sea letter is specified as required by the treaty with Holland. Here is the text from Annals:

The Revolutionary Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States, Volume 2

Form of the Passport to be given to Ships or Vessels, conformable to the Thirtieth Article of this Treaty.*[Note *: * MSS. Dep. of State.]

February 6, 1778.

To all who shall see these presents, greeting:

Be it known that leave and permission are hereby given to A. B., master and commander of the ship or vessel called –, of the (city, town, etc.), of –, burden –, tons or thereabouts, lying at present in the port or haven of –, bound for –, and laden with –, to depart and proceed with his said ship (or vessel) on the said voyage; such ship (or vessel) having been visited and the said master and commander having made oath before the proper officer that the said ship (or vessel) belongs to one (or more) of the subjects, people, or inhabitants of –, and to him (or them) only.

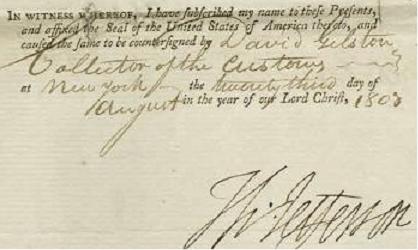

In witness whereof we have subscribed our names to these presents and affixed the seal of our arms thereto, and caused the same to be countersigned by –, at –, this –day of –, in the year of our Lord Christ –.

I have found additional sea letters with the phrase “in the year of our Lord Christ” pre-printed. These are similar to the images signed by John Adams and James Madison which Barton presented at Liberty. Click this link to see an entire document with all four languages (Dutch, English, French and Spanish). Then see below for two closer views:

Adams, Madison and every other President signed these forms on behalf of countless vessels sailing into foreign waters. That Presidents signed their names to form letters with language required by treaty is simply not an indicator of some special recognition of Christ. Although the Americans were not antagonistic to including this diplomatic language in their treaties, they were not breaking new religious or political ground. As I noted in the prior post, other nations, including France and Holland, used this language long before the United States did as a new nation.

I suppose if you don’t take into account that the various treaties specified the exact language to be used, and you aren’t aware that Jefferson said sea letters are “the creatures of treaties,” then one might believe that Jefferson and early Presidents wanted to bring Christ into the important business of shipping passports.

I should add that I don’t claim to be a historian. Rather, I am taking the suggestion Mr. Barton made to Liberty University students. He told them in his speech not to take things for granted. He said go back to the original documents and explore the facts for yourself. Having done that, I disagree with Mr. Barton. In no reasonable use of the language can it be said that the early presidents signed presidential acts with the designation “in the year of our Lord Christ.”

For other posts examining similar claims, see this link.