UPDATE (1/12/18) – Last night, SAMHSA Asst. Secretary Elinore McCance-Katz released a statement about the termination of NREPP. The full statement is at the link and the end of this post. She also held a brief conference call with reporters. Although I wasn’t on it, I communicated with two people on the call. On the call and in her written statement, Dr. McCance-Katz criticized the NREPP. On the call, she was quoted by a reporter on the call as saying, “We in the Trump administration are not going to sit back and let people die,” she said, which will happen “if we leave things up on the website that don’t help people.”

There still is no time table for the implementation of the Policy Lab or any new approach. The statement is light on specifics. When I ask about when and how this is going to happen, I have gotten no responses. I hope to have another post later today with reactions to the Asst. Secretary’s remarks and am holding out hope that SAMHSA might address the issues of timing and implementation.

………………………………..

(Original post begins here)

One thing is clear. The National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs & Practices contract has been terminated. SAMHSA’s statement about the registry first posted here on this blog is now on the NREPP website (see the statement in red below):

What Now?

In one form or another, the question on the minds of many mental health researchers and advocates is “what now?” After I received the statement above on 1/8, I asked a SAMHSA spokesman when researchers would be able to submit programs or update new programs. There has been no answer. It appears that SAMHSA discontinued NREPP even though the agency is not prepared to “reconfigure its approach” to evidence-based practice. Thus far, something is being replaced by nothing.

Media accounts of NREPP’s demise reflect the reaction of the mental health community. The Week‘s headline this morning reads, “Trump officials froze a federal database of addiction and mental health treatments. Nobody’s sure why.”

On Tuesday, Think Progress led with “Without warning, the government just ended a registry of mental illness and drug abuse programs.” The subtitle? “And didn’t bother to warn program participants ahead of time.”

Yesterday, the Boston Globe‘s health news service Stat began:

The Trump administration has abruptly halted work on a highly regarded program to help physicians, families, state and local government agencies, and others separate effective “evidence-based” treatments for substance abuse and behavioral health problems from worthless interventions.

Also out this morning, the Washington Post covers much of the same ground but provides no details from SAMHSA about when the new process will begin.

I say again, SAMHSA replaced something with nothing and did so in the middle of an addiction epidemic.

Rep. Grace Meng Wants to Know What’s Going On with NREPP

Rep. Grace Meng represents the Sixth District of New York and is a member of the House Appropriations Committee. On January 5, unaware of the impending controversy over NREPP, she wrote SAMHSA to praise NREPP and ask how she could help support the registry. She closed her letter by saying,

Again, thank you for the NREPP. I feel that the registry and its website are crucial public health tools. Respectfully, I wish to know how you will grow the NREPP and its website, how you intend to review more opioid abuse-specific programs, and how I may be of help to you in these endeavors.

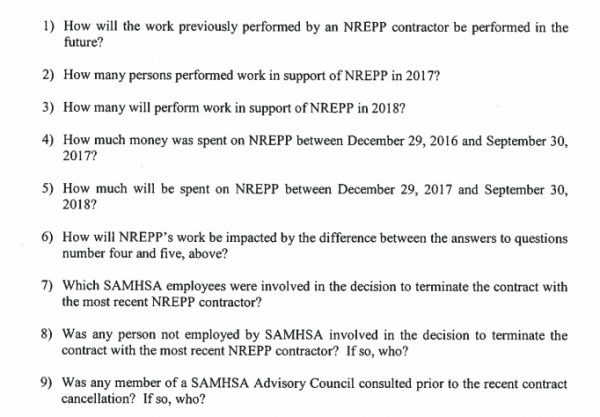

When Rep. Meng learned about the NREPP’s termination, she followed up with another letter on January 8 requesting the answers to several questions. The first question was “Why, with specificity, was this contract terminated?” That was followed by nine additional questions:

These are good questions. I would add, why did SAMHSA terminate NREPP when it appears that SAMHSA doesn’t have another evidence-based process ready to go?

For background, see my first post on the termination of NREPP.

…………..

Statement of Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use regarding the National Registry of Evidence Programs and Practices and SAMHSA’s new approach to implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs)

Thursday, January 11, 2018

SAMHSA and HHS are committed to advancing the use of science, in the form of data and evidence-based policies, programs and practices, to improve the lives of Americans living with substance use disorders and mental illness and of their families.

People throughout the United States are dying every day from substance use disorders and from serious mental illnesses. The situation regarding opioid addiction and serious mental illness is urgent, and we must attend to the needs of the American people. SAMHSA remains committed to promoting effective treatment options for the people we serve, because we know people can recover when they receive appropriate services.

SAMHSA has used the National Registry of Evidence Programs and Practices (NREPP) since 1997. For the majority of its existence, NREPP vetted practices and programs submitted by outside developers – resulting in a skewed presentation of evidence-based interventions, which did not address the spectrum of needs of those living with serious mental illness and substance use disorders. These needs include screening, evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, psychotherapies, psychosocial supports and recovery services in the community.

The program as currently configured often produces few to no results, when such common search terms as “medication-assisted treatment” or illnesses such as ”schizophrenia” are entered. There is a complete lack of a linkage between all of the EBPs that are necessary to provide effective care and treatment to those living with mental and substance use disorders, as well. If someone with limited knowledge about various mental and substance use disorders were to go to the NREPP website, they could come away thinking that there are virtually no EBPs for opioid use disorder and other major mental disorders – which is completely untrue.

They would have to try to discern which of the listed practices might be useful, but could not rely on the grading for the listed interventions; neither would there be any way for them to know which interventions were more effective than others.

We at SAMHSA should not be encouraging providers to use NREPP to obtain EBPs, given the flawed nature of this system. From my limited review – I have not looked at every listed program or practice – I see EBPs that are entirely irrelevant to some disorders, “evidence” based on review of as few as a single publication that might be quite old and, too often, evidence review from someone’s dissertation.

This is a poor approach to the determination of EBPs. As I mentioned, NREPP has mainly reviewed submissions from “developers” in the field. By definition, these are not EBPs because they are limited to the work of a single person or group. This is a biased, self-selected series of interventions further hampered by a poor search-term system. Americans living with these serious illnesses deserve better, and SAMHSA can now provide that necessary guidance to communities.

We are now moving to EBP implementation efforts through targeted technical assistance and training that makes use of local and national experts and will that assist programs with actually implementing services that will be essential to getting Americans living with these disorders the care and treatment and recovery services that they need.

These services are designed to provide EBPs appropriate to the communities seeking assistance, and the services will cover the spectrum of individual and community needs including prevention interventions, treatment and community recovery services.

We must do this now. We must not waste time continuing a program that has had since 1997 to show its effectiveness.

But yet we know that the majority of behavioral health programs still do not use EBPs: one indicator being the lack of medication-assisted treatment, the accepted, life-saving standard of care for opioid use disorder, in specialty substance use disorder programs nationwide.

SAMHSA will use its technical assistance and training resources, its expert resources, the resources of our sister agencies at the Department of Health and Human Services, and national stakeholders who are consulted for EBPs to inform American communities and to get Americans living with these disorders the resources that they deserve.