The 50th anniversary of the March of Washington for Jobs and Freedom is being commemorated this weekend through August 28. The march took place on August 28, 1963. Free At Last by DC Talk (from one my favorite all-time CDs) samples Martin Luther King Jr.’s I Have a Dream Speech (which I will post on Wednesday).

DC Talk members Toby Mac, Kevin Max and Michael Tait attended Liberty University. How sad it is that Liberty University is hosting the Institute on the Constitution’s course on their television network.

Tag: liberty university

Dean of Liberty Law School Says Islam Not Protected by the First Amendment

Prospective Christian law students pay attention.

Mat Staver, Dean of the Liberty University Law School told OneNewsNow, the “news service” of the American Family Association that Islam is more political ideology than religion and as such does not merit the same religious liberty protections. Staver said

“One of the issues, however, that needs to be considered is whether or not there will be much emphasis placed on advancing the Muslim cause,” he notes. “Certainly that could be a concern to many people around the country.”

He explains why that should be a concern in a law school.

“Islam is a political ideology. Certainly it takes characteristics of religion, but by and large, at its core, both in the United States and around the world, it is a political ideology,” Staver asserts. “Consequently, to use the same kind of laws for an advancement of a political ideology that you would for religious liberty could eventually cause some concerning issues that we want to address.”

Thomas Jefferson certainly disagreed with this analysis. When Jefferson commented on his Virginia law on religious freedom, he said the law was meant to cover all religions. Specifically, Jefferson wrote:

The bill for establishing religious freedom, the principles of which had, to a certain degree, been enacted before, I had drawn in all the latitude of reason & right. It still met with opposition; but, with some mutilations in the preamble, it was finally past; and a singular proposition proved that it’s protection of opinion was meant to be universal. Where the preamble declares that coercion is a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, an amendment was proposed, by inserting the word “Jesus Christ,” so that it should read “departure from the plan of Jesus Christ, the holy author of our religion” the insertion was rejected by a great majority, in proof that they meant to comprehend, within the mantle of it’s protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan [Islam], the Hindoo, and infidel of every denomination.

The Virginia statute is not the First Amendment but it is clear that James Madison, acting in sympathy with Jeffersonian views, intended the same scope for the First Amendment.

Another frightening aspect of Staver’s reasoning is that it could easily be applied to other religions, including Christianity. Churches that pass out political guides and organize members to vote GOP could easily be considered to be purveyors of a political ideology.

Turn the other fist

As if we needed another validation of the New Testament adage: Money is the root of all sorts of evil.

Donald Trump at Liberty University.

I guess I have been misreading Matthew 5:39 all these years.

The new evangelical creed: Turn the other fist.

Liberty University: Home of Greed Pride.

On David Barton's claim that Unitarians were "a very evangelical Christian denomination"

David Barton told Liberty University students in their September 9 chapel that Unitarians were at one time “a very evangelical Christian denomination.” In his effort to define what he called modernism, he said this about the Unitarians the late 18th and early 19th century:

And the example of that is what happens when you look at Universalist Unitarians; certainly not a denomination that conforms to biblical truth in any way but as it turns out, we have a number of Founding Fathers who were Unitarians. So we say, oh wait, there’s no way the Founding Fathers could have been Christians; they were Unitarians. Well, unless you know what a Unitarian was in 1784 and what happened to Unitarians in 1819 and 1838 and unless you recognize they used to be a very evangelical Christian denomination, we look at what they are today and say the Founding Fathers were Unitarians, and say, there’s no way they were Christians. That’s modernism; that’s not accurate; that’s not true.

Last week, I briefly examined Barton’s claim that Unitarians were a “very evangelical denomination” with the help of college professor and attorney Jon Rowe. In a 2007 post, Rowe noted that Unitarians during the era of the Founding Fathers denied the Trinity and the deity of Christ. While Unitarians used the Bible to come to their conclusions, one cannot call them evangelical in any meaningful or current sense of the word.

I also asked two Grove City College colleagues with expertise in religious history, Gillis Harp (professor of history) and Paul Kemeny (associate professor of religion and humanities), to react to Barton’s claim about the Unitarians. First, Dr. Kemeny contradicted Barton, saying:

To call nineteenth-century Unitarians a “every evangelical Christian denomination” is like calling a circle a square. While many were deeply pious, Unitarians rejected the deity of Christ and consequently the Trinity. Since the common sense meaning of “evangelical Christian” usually entails an affirmation of Christ’s deity and by implication the Trinity, it strikes me as a rather oddly creative use of the term to suggest Unitarians were “evangelical Christians.” The Unitarians’ early nineteenth-century critics, such as orthodox Congregationalist theologian Leonard Woods, would likely be surprised to learn the Unitarians were actually “evangelical Christians after all.

As Kemeny notes, the orthodox theologians of the time did not think of Unitarians as orthodox. The Congregationalists of the eighteenth century were in dispute with their fellows who were moving in the Unitarian ways. For instance, President John Adams is often listed as a Congregationalist, but, as I documented previously, his views were decidedly Unitarian.

Dr. Harp also discounted Barton’s theory, saying

It is misleading to refer to early 19th century Unitarians as ‘evangelical.’ If Barton means that they were far more orthodox on many basic doctrinal matters than are Unitarians today – then, sure, one can say that. But belief in the incarnation and substitutionary atonement are both essential to evangelicalism and these were both firmly repudiated by all Unitarians in this period. Some Unitarians certainly continued to follow evangelical personal habits (daily prayer, Bible study, promoting evangelism) but that doesn’t make them evangelical doctrinally.

Christian scholars Harp and Kemeny agree that the claim is faulty. What about the original sources? If Unitarians of the era were evangelical in doctrine, perhaps this would show up in their writings. However, even a cursory examination of the leading Unitarian thinkers demonstrates that Barton is incorrect.

Barton cites Jared Sparks as a man who said George Washington was a Christian in the evangelical sense. However, Sparks was a leading Unitarian. Sparks’ ordination to the ministry in 1819 was the occasion for William Ellery Channing to preach a sermon outlining Unitarian beliefs in a break with the more orthodox Congregationalists.

Sparks was also the editor of the Unitarian Miscellany and Christian Monitor. In an 1821 edition, he explained the Unitarian position on Christ.

Unitarians believe, that Jesus Christ was a messenger commissioned from heaven to make a revelation, and communicate the will of God to men. They all agree, that he was not God; that he was a distinct being from the Father, and subordinate to him; and that he received from the Father all his power, wisdom, and knowledge. (p. 13)

Although unitarians do not believe Christ to be God, because they think such a doctrine at variance with reason and scripture, yet they believe him to have been authorized and empowered to make a divine revelation to the world. We believe in the divinity of his mission, but not of his person. We consider all he has taught as coming from God; we receive his commands, and rely on his promises, as the commands and promises of God. In his miracles we see the power of God; in his doctrines and precepts we behold the wisdom of God; and in his life and character we see a bright display of every divine virtue. Our hope of salvation rests on the truths lie has disclosed, and the means he has pointed out. We believe him to be entitled to our implicit faith, obedience, and submission, and we feel towards him all the veneration, love, and gratitude, which the dignity of his mission, the sublime purity ot his character, and his sufferings for the salvation of men, justly demand. But we do not pay him religious homage, because we think this would be derogating from the honour and majesty of the Supreme Being, who, our Saviour himself has told us, is the only proper object of our adoration and worship. (p. 15-16)

Regarding sin, Unitarians denied original sin and consequently the need for Christ’s atonement to pay the penalty for sin. Again in 1821, Sparks wrote:

We have only room to state, that we do not believe “the guilt of Adam’s sin was imputed, and his corrupted nature conveyed to all his posterity;” nor that there is in men any “original corruption, whereby they are utterly indisposed, disabled, and made opposite to all good, and wholly inclined to all evil.” (p. 19)

Disputes between trinitarians and the anti-trinitarians (as unitarians were often called) raged in eighteenth century New England. Historian E. Brooks Holifield wrote in his book Theology in America that the divinity of Christ was in doubt among New England clergy as early as 1735, adding

By 1768, Samuel Hopkins could claim that most of the ministers of Boston disbelieved the doctrine of the divinity of Christ. By 1785, James Freeman succeeded in leading the Episcopal congregation at King’s Chapel in Boston to delete Trinitarian views from their liturgy. (p. 199)

In his speech to Liberty University quoted above, Barton refers to 1784 as a point of reference for what Unitarians were. Perhaps he has this transition at King’s Chapel in mind when the church went from Anglican doctrine to Unitarian beliefs. The minister at the time, James Freeman, considered the church Anglican. However, in another sign that orthodox leaders of the day did not consider Unitarian views to be in line with traditional doctrine, the local Bishop refused to ordain Freeman in the Anglican church.

A question for Mr. Barton: Since the Unitarians at the time took pains to distinguish themselves from orthodoxy and the orthodox leaders of the day did not consider unitarian beliefs to be what we would today call evangelical, why would we dispute them now and call them “very evangelical?”

David Barton: Did Early Presidents Sign Documents "In the Year of Our Lord Christ?"

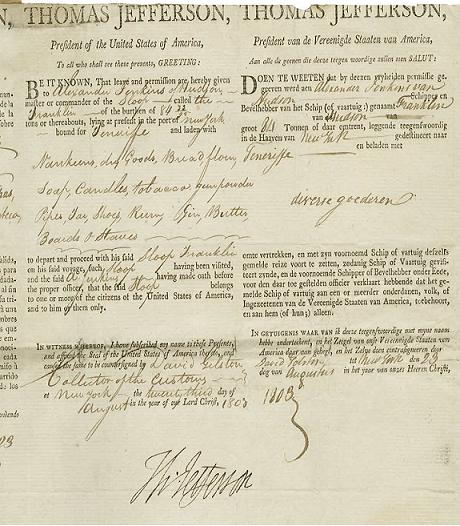

On September 9, David Barton spoke to students at Liberty University during their chapel service. Last week I addressed several claims Barton made during the first five minutes of his talk. Today, I want to follow up with more detail about Barton’s claim that Thomas Jefferson and other early Presidents signed official presidential documents with the closing “In the year of our Lord Christ.” Barton points to this phrase as evidence that the early Presidents “had Jesus Christ in the center of what they did.”

Earlier this year, I demonstrated that a document on the Wallbuilders website dated 1807 and signed by Thomas Jefferson is a passport, also called a sea letter, needed by ships at the time to indicate that they were no threat to friend or foe as a combat ship. The wording of the sea letter signed by Jefferson was required by a treaty with Holland. Sea letters were in common use, so much so that Congress authorized the printing of a form for this use with the treaty language preprinted. The language specified in the treaty with Holland included the phrase, “In the year of our Lord Christ” and only required the person completing the form to include information about the ship, the cargo, the destination and the correct date.

This was a perfunctory duty of the President at the time, causing John Adams to lament to his wife Abigail in a letter that his fate was to sign “Thousands of sea letters, Mediterranean passes, and commissions and patents to sign; no company — no society.”

Thomas Jefferson was once asked about the proper use of a sea letter by Secretary of Treasury Albert Gallatin. In his January 26, 1805 reply, it is clear that the document is not something he or the Congress developed, saying

The question arising on Mr. Simons’ letter of January 10th is whether sea-letters shall be given to the vessels of citizens neither born nor residing in the United States. Sea-letters are the creatures of treaties. No act of the ordinary legislature requires them. The only treaties now existing with us, and calling for them, are those with Holland, Spain, Prussia, and France. In the two former we have stipulated that when the other party shall be at war, the vessels belonging to our people shall be furnished with sea-letters; in the two latter that the vessels of the neutral party shall be so furnished. France being now at war, the sea-letter is made necessary for our vessels; and consequently it is our duty to furnish them. (my emphasis)

If you search through the Annals of Congress (1774-1875), you will find 8 citations with the exact phrase, “in the year of our Lord Christ.” All of them are used in a treaty (Holland, Morocco, Japan). The exact form for the sea letter is specified as required by the treaty with Holland. Here is the text from Annals:

The Revolutionary Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States, Volume 2

Form of the Passport to be given to Ships or Vessels, conformable to the Thirtieth Article of this Treaty.*[Note *: * MSS. Dep. of State.]

February 6, 1778.

To all who shall see these presents, greeting:

Be it known that leave and permission are hereby given to A. B., master and commander of the ship or vessel called –, of the (city, town, etc.), of –, burden –, tons or thereabouts, lying at present in the port or haven of –, bound for –, and laden with –, to depart and proceed with his said ship (or vessel) on the said voyage; such ship (or vessel) having been visited and the said master and commander having made oath before the proper officer that the said ship (or vessel) belongs to one (or more) of the subjects, people, or inhabitants of –, and to him (or them) only.

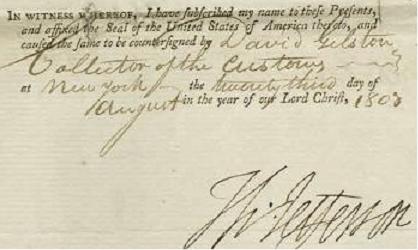

In witness whereof we have subscribed our names to these presents and affixed the seal of our arms thereto, and caused the same to be countersigned by –, at –, this –day of –, in the year of our Lord Christ –.

I have found additional sea letters with the phrase “in the year of our Lord Christ” pre-printed. These are similar to the images signed by John Adams and James Madison which Barton presented at Liberty. Click this link to see an entire document with all four languages (Dutch, English, French and Spanish). Then see below for two closer views:

Adams, Madison and every other President signed these forms on behalf of countless vessels sailing into foreign waters. That Presidents signed their names to form letters with language required by treaty is simply not an indicator of some special recognition of Christ. Although the Americans were not antagonistic to including this diplomatic language in their treaties, they were not breaking new religious or political ground. As I noted in the prior post, other nations, including France and Holland, used this language long before the United States did as a new nation.

I suppose if you don’t take into account that the various treaties specified the exact language to be used, and you aren’t aware that Jefferson said sea letters are “the creatures of treaties,” then one might believe that Jefferson and early Presidents wanted to bring Christ into the important business of shipping passports.

I should add that I don’t claim to be a historian. Rather, I am taking the suggestion Mr. Barton made to Liberty University students. He told them in his speech not to take things for granted. He said go back to the original documents and explore the facts for yourself. Having done that, I disagree with Mr. Barton. In no reasonable use of the language can it be said that the early presidents signed presidential acts with the designation “in the year of our Lord Christ.”

For other posts examining similar claims, see this link.