In addition to being Independence Day, this is the day that John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died within hours of each other on July 4, 1826.

On this day in 1826, former Presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who were once fellow Patriots and then adversaries, die on the same day within five hours of each other.

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were friends who together served on the committee that constructed the Declaration of Independence, but later became political rivals during the 1800 election. Jefferson felt Adams had made serious blunders during his term and Jefferson ran against Adams in a bitter campaign. Two men stopped communicating and Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush wanted to encourage them to reconcile. Rush was on good terms with both Adams and Jefferson and set about to help them mend the distance. In his letter to Adams on October 17, 1809, Rush used the device of a dream to express his wish that Adams and Jefferson would again resume communications. This letter is part of a remarkable sequence of letters which can be read here. In this portion, Rush suggests his “dream” of a Jefferson-Adams reunion.

“What book is that in your hands?” said I to my son Richard a few nights ago in a dream. “It is the history of the United States,” said he. “Shall I read a page of it to you?” “No, no,” said I. “I believe in the truth of no history but in that which is contained in the Old and New Testaments.” “But, sir,” said my son, “this page relates to your friend Mr. Adams.” “Let me see it then,” said I. I read it with great pleasure and herewith send you a copy of it.

“1809. Among the most extraordinary events of this year was the renewal of the friendship and intercourse between Mr. John Adams and Mr. Jefferson, the two ex-Presidents of the United States. They met for the first time in the Congress of 1775. Their principles of liberty, their ardent attachment to their country, and their views of the importance and probable issue of the struggle with Great Britain in which they were engaged being exactly the same, they were strongly attracted to each other and became personal as well as political friends. They met in England during the war while each of them held commissions of honor and trust at two of the first courts of Europe, and spent many happy hours together in reviewing the difficulties and success of their respective negotiations. A difference of opinion upon the objects and issue of the French Revolution separated them during the years in which that great event interested and divided the American people. The predominance of the party which favored the French cause threw Mr. Adams out of the Chair of the United States in the year 1800 and placed Mr. Jefferson there in his stead. The former retired with resignation and dignity to his seat at Quincy, where he spent the evening of his life in literary and philosophical pursuits, surrounded by an amiable family and a few old and affectionate friends. The latter resigned the Chair of the United States in the year 1808, sick of the cares and disgusted with the intrigues of public life, and retired to his seat at Monticello, in Virginia, where he spent the remainder of his days in the cultivation of a large farm agreeably to the new system of husbandry. In the month of November 1809, Mr. Adams addressed a short letter to his friend Mr. Jefferson in which he congratulated him upon his escape to the shades of retirement and domestic happiness, and concluded it with assurances of his regard and good wishes for his welfare. This letter did great honor to Mr. Adams. It discovered a magnanimity known only to great minds. Mr. Jefferson replied to this letter and reciprocated expressions of regard and esteem. These letters were followed by a correspondence of several years in which they mutually reviewed the scenes of business in which they had been engaged, and candidly acknowledged to each other all the errors of opinion and conduct into which they had fallen during the time they filled the same station in the service of their country. Many precious aphorisms, the result of observation, experience, and profound reflection, it is said, are contained in these letters. It is to be hoped the world will be favored with a sight of them. These gentlemen sunk into the grave nearly at the same time, full of years and rich in the gratitude and praises of their country (for they outlived the heterogeneous parties that were opposed to them), and to their numerous merits and honors posterity has added that they were rival friends.

With affectionate regard to your fireside, in which all my family join, I am, dear sir, your sincere old friend,

BENJN: RUSH

It is not clear to me that Rush had an actual dream. He may have used the device of a dream to prod his friend into reconciliation with Jefferson. On more than one prior occasion, Rush communicated his views via writing about them as dreams. For instance, Rush responded to a political question from Adams in a February 20, 1809 letter via a dream narrative. Adams responded on March 4, 1809 praising Rush’s wit and asked for a dream about Jefferson:

Rush,—If I could dream as much wit as you, I think I should wish to go to sleep for the rest of my Life, retaining however one of Swifts Flappers to awake me once in 24 hours to dinner, for you know without a dinner one can neither dream nor sleep. Your Dreams descend from Jove, according to Homer.

Though I enjoy your sleeping wit and acknowledge your unequalled Ingenuity in your dreams, I can not agree to your Moral. I will not yet allow that the Cause of “Wisdom, Justice, order and stability in human Governments” is quite desperate. The old Maxim Nil desperandum de Republica is founded in eternal Truth and indispensable obligation.

Jefferson expired and Madison came to Life, last night at twelve o’clock. Will you be so good as to take a Nap, and dream for my Instruction and edification a Character of Jefferson and his Administration?

Another reason that I question whether it was an actual dream is because a draft of this letter demonstrates that Rush considered another literary device for his prophecy. A footnote in Lyman Butterfield’s compilation of Rush’s letter reads:

In the passage that follows, BR [Benjamin Rush] made his principal plea to Adams to make an effort toward reconciliation with Jefferson. That pains were taken in composing the plea is shown by an autograph draft of the letter, dated 16 Oct. in Hist. Soc. Penna., Gratz Coll. In the draft BR originally wrote, and then crossed out, the following introduction to his dream history: “What would [you omitted] think of some future historian of the United States concluding one of his chapters with the following paragraph?” The greater verisimilitude of the revision adds much to the effectiveness of this remarkable letter. (Butterfield, L.H., The Letters of Benjamin Rush, Vol. II, 1793-1813, Princeton Univ. Press, 1951, p. 1023)

Apparently, Rush wanted to get this message to Adams and chose to use a device already requested by Adams, instead of an appeal to legacy via the reference to the history books.

In any case, real dream or not, Adams liked the proposition and replied to Rush on October 25, 1809, about the “dream” saying,

A Dream again! I wish you would dream all day and all Night, for one of your Dreams puts me in spirits for a Month. I have no other objection to your Dream, but that it is not History. It may be Prophecy. There has never been the smallest Interruption of the Personal Friendship between me and Mr. Jefferson that I know of. You should remember that Jefferson was but a Boy to me. I was at least ten years older than him in age and more than twenty years older than him in Politicks. I am bold to say I was his Preceptor in Politicks and taught him every Thing that has been good and solid in his whole Political Conduct. I served with him on many Committees in Congress in which we established some of the most important Regulations of the Army &c, &c, &c

Jefferson and Franklin were united with me in a Commission to the King of France and fifteen other Commissions to treat with all the Powers of Europe and Africa. I resided with him in France above a year in 1784 and 1785 and met him every day at my House in Auteuil at Franklins House at Passy or at his House in Paris. In short we lived together in the most perfect Friendship and Harmony.

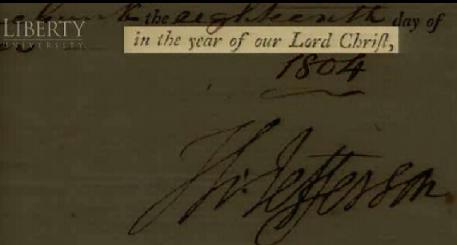

Although in a less poetic manner, Rush also wrote Jefferson to suggest a resumption of friendship. Although it took awhile (1812), Adams and Jefferson did resume correspondence. As predicted by Rush, they carried on a vigorous correspondence until late in their lives regarding their personal and political lives. Then 50 years after July 4, 1776, Jefferson and Adams “sunk into the grave nearly at the same time, full of years and rich in the gratitude and praises of their country…”*

Much of this post was adapted from a prior post on John Adams and the Holy Ghost letter and published on this blog May 31, 2011.