Commenter Evan recently posted a link to a informative powerpoint produced by colleague Morten Frisch regarding his study of social and family factors associated with homosexual and heterosexual marriage in Denmark. Morten is no stranger to this blog as he commented at length regarding the Cameron’s biased attempt to estimate homosexual lifespans. I reviewed this study for a Washington Times article (the WT link is disabled but it is here)and believe it is a significant contribution to the literature regarding causal factors associated with sexual orientation.

I would like to look at the significant findings in Frisch’s study in relationship to predictions made by reparative drive theory. According to the powerpoint, the purpose for the study was

To use a unique national set of demographic data free of selection bias to

-identify possible childhood family correlates of adult sexual orientation and partner choices

-evaluate the fraternal birth order (FBO) hypothesis (Blanchard) for male homosexuality

Regarding the latter purpose, the study found no evidence to support the FBO. What I want to do now is reproduce a few of the slides in light of predictions from reparative theory. Reparative theory proposes that disruption in the same-sex parent relationship in the crucial years of gender identity formation is responsible for homosexuality as a “gender identity problem” (Joe Nicolosi used to call homosexuality a gender identity disorder). His newer iteration of the theory refers to male homosexual “enactment” as deriving from feeling cut off from authentic masculinity. This deficit is located in a failure of the boy to successfully disidentify with mother and identify and bond with father between 18 and 36 months of age. Rejection from male peers builds on the bonding failure resulting in an eventual experience of same-sex attractions in a false and futile effort to return to masculinity. He has less to say about female homosexuality and most reparative therapists say that just about anything can lead to lesbianism as long as it is traumatic in some way or a deficit of upbringing.

Based on these premises, we would expect research on large groups of homosexuals to show an increase in problems during those crucial periods of early childhood. Further, we would expect the differences between groups to be large since reparative therapists say that the environmental experiences are necessary causes of same-sex attraction. With this in mind, let’s look at the Frisch results.

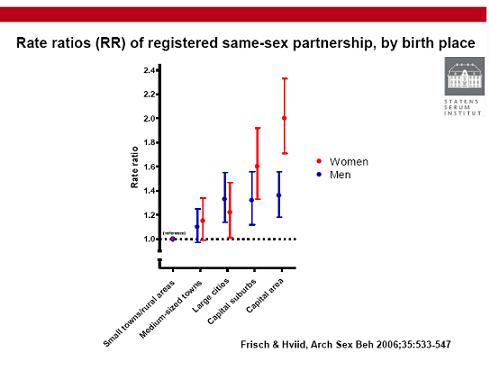

Birth place and marriage

On all of these tables, one (1) is the baseline and deviation from one is considered to be an increase or decrease in likelihood of homosexual partnership. In this case, the likelihood of same-sex partner choice goes up with the urbanicity of birth place. It is hard to know what this means. One might suppose that attitudes toward same-sex marriage are more liberal in the urban area if one assumes people are married where they are born. In a smaller country like Denmark, it seems that gay people in the rural areas might just move to the city where attitudes are more accepting. Perhaps, the social attitudes in the area where one grows up plays a role as well.

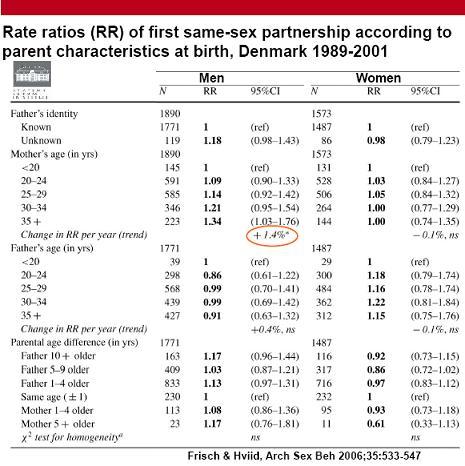

Parental characteristics

First note that none of the variables here are significant for women and only one is for men – mother’s age. There is a slight increase in odds of homosexual marriage for men if one’s mother was over 35 at birth. I do not see any clear theoretical connection for this finding. However, apropos to this post, note that awareness of the identity of one’s father has no significant impact on marital direction. A reparative paradigm would expect disruptions or ambiguity of paternal identification to lead to an increase in homosexual partnering.

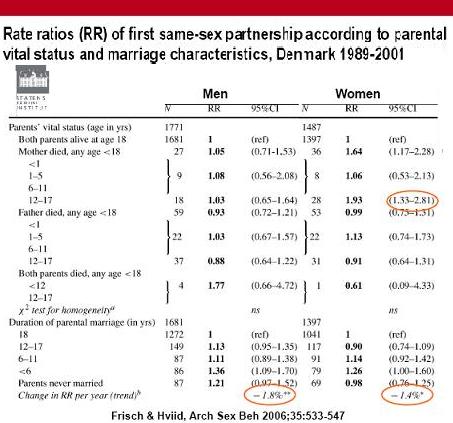

Parental vital status and marriage characteristics

Reparative theory would predict disruptions in the same-sex parent bond in early childhood. As indicated by parental death, Frisch does not find the predicted disruptions. First of all, such circumstances for men or women are infrequent (only 22 cases each of paternal death before age 11) and second, there is no relationship to partnering in males. In females, the relationship to partnering is not in the early childhood years but during adolescence. As with all of these differences, the effect size is quite small so the variable does not account for much variation between gay and straight partnering.

Regarding parental marriages, I am a bit unclear how this finding relates to reparative drive theory. I initially wrote that there is a very small effect of short parental marriages for both men and women. However, I asked Morten to read this summary prior to publication and he took some exception to this point. He wrote,

Actually, there is a 36% higher likelihood of same-sex marriage among boys whose parents’ marriage lasted less than 6 years compared with boys whose parents’ marriage remained intact until age 18 years, and the corresponding estimate was 26% higher same-sex marriage rates among girls whose parents’ marriage lasted less than 6 years compared with girls whose parents’ marriage remained intact until age 18 years. Our data on duration of parental marriage duration and, for boys, duration of father-absent cohabitation with mother obviously don’t prove anything in relation to the reparative theory, but they are not in conflict with it.

On the other hand, effect sizes calculated in the way I am used to seeing finds a trivial amount of variance.

The only marriage duration that related to homosexual marriage was the “less than 6 years” category.” It would be tempting to see this as meaning that the children were all under 6. However, in Denmark, it is not uncommon for couples to cohabitate, have a child and then get married. In other words, we cannot assume the ages of the children involved based on duration of marriage.

In any event, this finding, even if of some substance, would neither confirm nor disconfirm the specifics of reparative drive theory – especially in light of the data which do not find a push toward homosexual partnering among males who experienced father absence due to death or unknown identity.

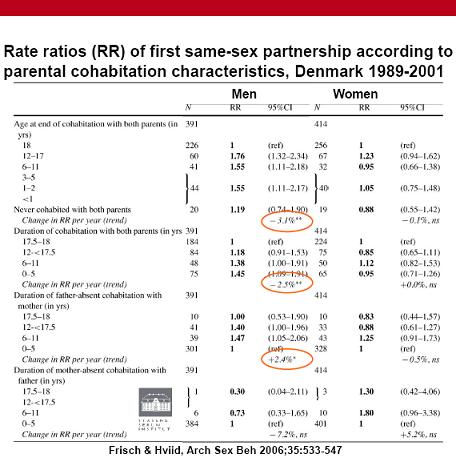

Parental cohabitation

This slide depicts data which seems more promising for a reparative theorist in that father absent cohabitation shows a slight relationship to partnering for males. However, if I was a reparative drive theorist, I would be disappointed. First, the number of gay males who experienced this factor is relatively small (80 of father absent cohabitation of between 6-17.5 years). Most partnered gays did not experience this event. Second, the effect is very small. If same-sex parent disruption was a necessary condition, might expect more dramatic results with application to both sexes.

I find myself in the unusual position of qualifying Morten’s conclusions. I think there is a need to qualify the factors by the non-significant results found. For instance, Morten lists father absence as a factor related to gay marriage. However, I would note that paternal absence via death was unrelated to outcome as was lack of knowledge of father’s identity.

On balance, I do not think Frisch and Hviid’s massive study of marriage choice provides significant support for reparative drive theory. If anything, the predicted findings are mixed.

If parental bonding and was massively and necessarily related to homosexual outcomes, it seems that some large study would find greater differences on the relevant dimensions. However, neither the recent Francis study nor the Wilson and Widom study of abuse and neglect demonstrate the expected results. While Frisch and Hviid report some impact of marital disruption, it is unclear what is the potent element of those events.