Due to time constraints, this post is less review than description of results. However, I wanted to post something on this study in advance of some commentary coming from Michael Bailey on the topic.

Here is the reference and abstract:

Abstract: The existence of genetic effects on gender atypical behavior in childhood and sexual orientation in adulthood and the overlap between these effects were studied in a population-based sample of 3,261 Finnish twins aged 33–43 years. The participants completed items on recalled childhood behavior and on same-sex sexual interest and behavior, which were combined into a childhood gender atypical behavior and a sexual orientation variable, respectively. The phenotypic association between the two variables was stronger for men than for women. Quantitative genetic analyses showed that variation in both childhood gender atypical behavior and adult sexual orientation was partly due to genetics, with the rest being explained by nonshared environmental effects. Bivariate analyses suggested that substantial common genetic and modest common nonshared environmental correlations underlie the co-occurrence of the two variables. The results were discussed in light of previous research and possible implications for theories of gender role

development and sexual orientation.

Common Genetic Effects of Gender Atypical Behavior in Childhood

and Sexual Orientation in Adulthood: A Study of Finnish Twins

K. Alanko, P. Santtila, N. Harlaar, K. Witting, M. Varjonen, P. Jern, A. Johansson, B. von der Pahlen, & N. K. Sandnabba. Arch Sex Behavior.

The sample was obtained via a registry maintained by the Central Population Registry of Finland which includes all twin pairs born in 1971 or earlier. The researchers requested information from the twins and received responses from 36% of those surveyed (3,604). For various reasons, the authors assume representativeness of their sample, although I think they might be open to some challenge on this point given the response rate.

The authors used Zucker’s Recalled Childhood Gender Identity/Gender Role Questionaire and Sell’s Assessment of Sexual Orientation. The SASO assesses both behavior and attractions via four items:

Item 1: During the past year, on average, how often were you sexually attracted to a man (woman for female participants)? The response alternatives were: never, less than 1 time per month, 1–3 times per month, 1 time per week, 2–3 times per week, 4–6 times per week, daily. Item 2: During the past year, on average, how often did you have sexual contact with a man (woman for female participants)? The response alternatives were the same as for Item 1 above. Item 3: How many different men (women for female participants) have you had sexual contact with during the past year? Item 4: During the past year, on average, how many different men (women for female participants) have you felt sexually attracted to? The response alternatives to Items 3 and 4 were: none, 1, 2, 3–5, 6–10, 11–49, 50–99, 100C. The participants were given numerical scores so that a response of ‘‘none’’/‘‘never’’ gave a score of 0 and a response of ‘‘100 or more’’/‘‘daily’’ gave a score of 7.

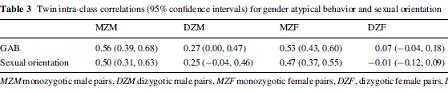

Here are the correlations of twins sharing traits of sexual orientation and gender atypical behavior.

Correlations were higher for identical twins than fraternal twins for both traits, especially for women. About the genetic contribution to GAB and sexual orientation, the authors said:

Significant genetic effects were found for women and men for both GAB and sexual orientation, as was our second hypothesis. The heritability estimates for childhood GAB were 51% and 29%, and for sexual orientation 45% and 50%, for women and men, respectively.

These numbers are higher than past studies and may be related to the nature of the sampling although this is not clear.

The authors also found a relationship between GAB and sexual orientation.

Our first aim was to study the phenotypic correlations between childhood GAB and adult sexual orientation. Significant correlations of moderate sizes were found, indicating that the two phenomena were related. The strength of the phenotypic association was higher for male participants, implying that childhood GAB was a stronger predictor of adult sexual orientation for men.

The authors note that these data in conjunction with past studies lead them to propose the possibility of several pathways to homosexual attractions.

There might, in other words, be different genotypes for different kinds of homosexuality. It might also be possible that the relative importance of shared environment and genetic influences vary during development. It is plausible that parents influence their children directly only as long as they live at home (Knafo et al., 2005; Plomin et al., 2001). Bailey et al. (2000) found that GAB predicted about 30% of the variance in men’s sexual orientation. As neither the phenotypic nor the genetic correlations were unity in the present sample, GAB preceded a homosexual orientation for some participants, whereas gender typicality preceded a homosexual orientation for other participants.

What did not show up was any significant role of shared environment for men. A small amount of the effect could be attributed to shared environment for women. Another data point suggesting that the pathways to adult sexual orientation are different for men and women.

Stay tuned…