There he goes again.

Nearing the anniversary of the largest pre-Civil War slave emancipation in U.S. history, David Barton is again claiming that Thomas Jefferson could not free his slaves because Virginia law did not allow it. He made the claim this week in a WorldNetDaily article out on Tuesday. Barton said:

“They [Louisiana Democrats] purportedly separated themselves from Thomas Jefferson because he owned slaves,” Barton told WND. “However, they ignored the fact that African-American civil rights leaders in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries openly praised Jefferson for his repeated efforts to abolish slavery in the United States, and even around the world. They understood a reality that today’s shallow academics and uninformed activists ignore: Virginia state law did not allow Jefferson to free his slaves, despite his desire to do so. So he worked to free all slaves throughout all of the United States. Those efforts are worthy of commendation – something Louisiana Democrats refuse to do.” (emphasis added)

Barton and the author of the article Paul Bremmer are bothered by Louisiana Democrats because they renamed their annual Jefferson-Jackson dinner. The LA Dems said the move reflects “the progress of the party and the changing times.”

My point is not to defend the LA Dems; they can do whatever they want with their dinner. Rather, I want to point out again that Virginia law allowed slave owners to emancipate slaves after 1782, and many slave owners did so. With the 226th anniversary of the writing of Virginia plantation owner Robert Carter’s deed of manumission coming on August 1, it is a good time for the reminder.

Virginia’s law on manumission changed the law to allow slave owners to free slaves via a deed of manumission filed at the county court house or upon the death of the owner in a will. The entire Virginia law, passed in 1782, is reproduced at the end of this post (see also the laws of Virginia; scroll to page 39).

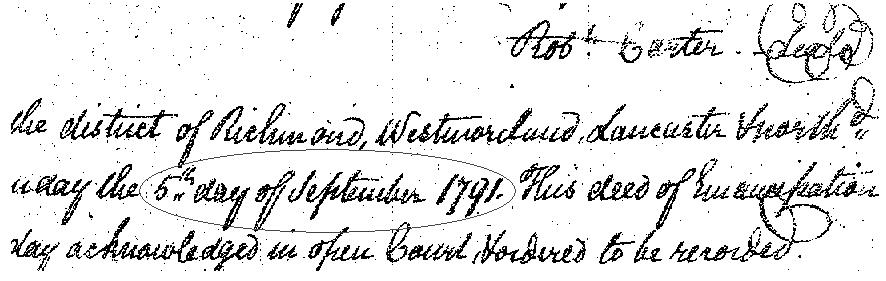

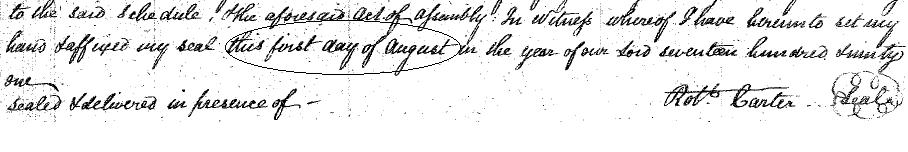

Robert Carter used that law to free his slaves. In his deed of manumission (linked at the end of the post), Carter said the following:

And whereas I have for some time past been convinced that to retain them [slaves] in slavery is contrary to the true principles of Religion & Justice, that therefore it was my Duty to manumit them, if it could be accomplished without infringing the laws of my Country, without being of disadvantage to my neighbors & the Community at large: And whereas the General Assembly for the Commonwealth of Virginia did in the year seventeen hundred eighty two enact a Law entitled “an Act to authorize the manumission of slaves” now be it remembered that the said Robert do under the said Act for myself my heirs my Executors & administrators emancipate from slavery all such my slaves in the aforesaid Schedule (as are under the age of forty-six years) but in a manner & form as hereafter particularly mentioned & set forth. (emphasis mine)

In his deed, Carter set in motion a process to free all 452 of his slaves over time. Some slaves were children and had to wait until they were adults or could be released to their freed parents. Others were older and required support. Adult able-bodied slaves were able to be freed the most easily. However, he and other slave owners took advantage of this law that was on the books during Jefferson’s time as a slave owner.

Laws were later changed to make it more difficult and less practical to emancipate slaves but there was a window when many slaves were freed. Given Jefferson’s lavish lifestyle and resultant debts, it might have been difficult to free his slaves but it was not because Virginia did not allow it. For some reason, Barton persists in repeating this error.

If Barton wanted to say it would have been difficult for Jefferson to free his slaves, he could just say so. Instead, he misrepresents Virginia law in

such a way as to remove the responsibility from Jefferson. There were times when Jefferson could have freed his slaves and other times when he would not have been able to, but it is wrong to say Virginia law didn’t allow it.

If Jefferson wanted to free his slaves so badly, why did he send slave catchers after those who ran away? Why did he buy and sell slaves? Why did he revel in the fact that slave women having slave babies increased his investment and wealth? In my book with Michael Coulter on Jefferson, we go into Jefferson as a slave owner in some detail.

For more on Jefferson, slavery, and Virginia slave laws, see the following resources.

A Challenge to WND and David Barton on Thomas Jefferson and Slavery

Kirk Cameron vs. Paul Finkelman on Jefferson and Slavery

Jefferson and Slavery: A Response to David Barton on the Glenn Beck Show, Part One

Jefferson and Slavery: A Response to David Barton on the Glenn Beck Show, Part Two

Jefferson and Slavery: A Response to David Barton on the Glenn Beck Show, Part Three

Robert Carter and Virginia’s Law on Manumission

Robert Carter III: A Forgotten Hero David Barton Doesn’t Want You to Remember

More Evidence David Barton is Wrong About Jefferson and Slavery: Robert Carter’s Emancipation Deed

August 1 – Robert Carter Appreciation Day

A Deed of Manumission

Pre-1820 Virginia Manumissions (an archive of numerous records of slaves freed in Virginia during the time Barton said the laws didn’t allow emancipation)

Virginia’s 1782 Law on Manumission

CHAP. XXI

An act to authorize the manumission of slaves.

I. WHEREAS application hath been made to this present general assembly, that those persons who are disposed to emancipate their slaves may be empowered so to do, and the same hath been judged expedient under certain restrictions: Be it therefore enacted, That it shall hereafter be lawful for any person, by his or her last will and testament, or by any other instrument in writing, under his or her hand and seal, attested and proved in the county court by two witnesses, or acknowledged by the party in the court of the county where he or she resides to emancipate and set free, his or her slaves, or any of them, who shall thereupon be entirely and fully discharged from the performance of any contract entered into during servitude, and enjoy as full freedom as if they had been particularly named and freed by this act.

II. Provided always, and be it further enacted, That all slaves so set free, not being in the judgment of the court, of sound mind and body, or being above the age of forty-five years, or being males under the age of twenty-one, or females under the age of eighteen years, shall respectively be supported and maintained by the person so liberating them, or by his or her estate; and upon neglect or refusal so to do, the court of the county where such neglect or refusal may be, is hereby empowered and required, upon application to them made, to order the sheriff to distrain and sell so much of the person’s estate as shall be sufficient for that purpose. Provided also, That every person by written instrument in his life time, or if by last will and testament, the executors of every person freeing any slave, shall cause to be delivered to him or her, a copy of the instrument of emancipation, attested by the clerk of the court of the county, who shall be paid therefor, by the person emancipating, five shillings, to be collected in the manner of other clerk’s fees. Every person neglecting or refusing to deliver to any slave by him or her set free, such copy, shall forfeit and pay ten pounds, to be recovered with costs in any court of record, one half thereof to the person suing for the same, and the other to the person to whom such copy ought to have been delivered. It shall be lawful for any justice of the peace to commit to the gaol of his county, any emancipated slave travelling out of the county of his or her residence without a copy of the instrument of his or her emancipation, there to remain till such copy is produced and the gaoler’s fees paid.

III. And be it further enacted, That in case any slave so liberated shall neglect in any year to pay all taxes and levies imposed or to be imposed by law, the court of the county shall order the sheriff to hire out him or her for so long time as will raise the said taxes and levies. Provided sufficient distress cannot be made upon his or her estate. Saving nevertheless to all and every person and persons, bodies politic or corporate, and their heirs and successors, other than the person or persons claiming under those so emancipating their slaves, all such right and title as they or any of them could or might claim if this act had never been made.