I talked about Robert Carter in a prior post. Carter set in motion a plan to free his slaves beginning on August 1, 1791. Fresh from the Northumberland District Court in Heathsville, Virginia, I have copies of the Deed of Gift which Carter filed on August 1, 1791. I will pull out a couple of pieces of it and then provide links to all the pages which you can click through to review.

David Barton wrote in The Jefferson Lies that Thomas Jefferson was unable to free his slaves due to Virginia law. However, in Getting Jefferson Right, we demonstrate that Virginia law changed in 1782 to allow emancipation both during an owner’s life and at his death. The law was in effect for 24 years until it was modified in 1806 to make manumission more complicated for the slaves.

It is one thing to examine the law, but it is another thing to see the law in application. Robert Carter, a wealthy plantation owner who also sat on the Governor’s Council, submitted a deed, in accord with the law, on September 5, 1791. The process would take years and involve other people Carter appointed when he left Virginia.

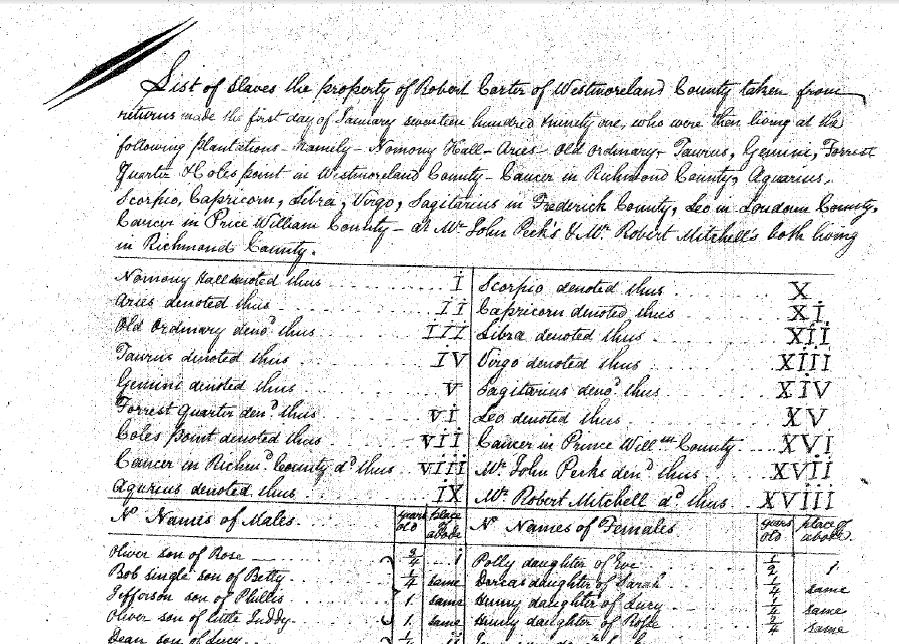

Carter wrote the Deed of Gift on August 1, 1791 and included a list of 452 of his slaves covering all or part of five pages. Slaves over age 45 would be handled in another manner. Page one is here so you can see the format of the deed:

First, Carter introduced the list, then provided a listing of his plantations and finally a list of his slaves by name, age and location.

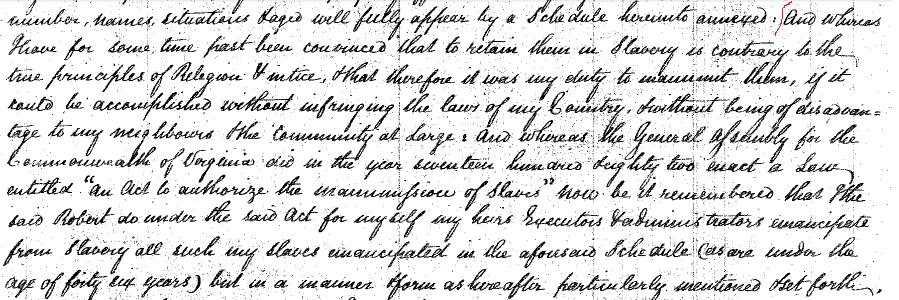

The next three pages contained an inventory of human beings and then on the fifth page of the deed, Carter provided his rationale and legal basis for the emancipation.

This section is quite important so I type it out here for easier reading (start at the red slash at the end of the first line):

And whereas I have for some time past been convinced that to retain them [slaves] in slavery is contrary to the true principles of Religion & Justice, that therefore it was my Duty to manumit them, if it could be accomplished without infringing the laws of my Country, without being of disadvantage to my neighbors & the Community at large: And whereas the General Assembly for the Commonwealth of Virginia did in the year seventeen hundred eighty two enact a Law entitled “an Act to authorize the manumission of slaves” now be it remembered that the said Robert do under the said Act for myself my heirs my Executors & administrators emancipate from slavery all such my slaves in the aforesaid Schedule (as are under the age of forty-six years) but in a manner & form as hereafter particularly mentioned & set forth.

Virginia law set age restrictions on manumissions and the older slaves would be handled differently. However, this document provides clear reference to the Virginia law passed in 1782 which allowed Carter to do what he listed here.

As recently as last week, David Barton told a radio audience that Jefferson could not free his slaves due to Virginia law. I don’t know how long it will take for someone in the Christian community to hold him accountable for this but the evidence is here that he is wrong.

Some have asked me why this matters. First of all, I would like to think that Christian leaders would not want to put out falsehoods. Second, I recently spoke to an African American pastor who told me that Barton’s whitewash of Jefferson’s record is offensive to him and his colleagues. According to this pastor, lifting up Jefferson as an abolitionist and civil rights champion hinders racial reconciliation within the greater Christian community.

Robert Carter’s entire Deed of Gift (click the links)

Page one, two, three, four, five, & six.

For more on Jefferson and slavery as well as other matters covered in David Barton’s recent book, see Getting Jefferson Right.